Boom Times, Not Boom Times

Learning about Ireland. Starting in Dublin. Finding some history. Some well remembered, some purposefully forgotten.

When I brought up the Celtic Tiger days to folks in Ireland, the consistent response was a general distrust of those days, almost an embarrassment. No one wanted to talk about it. They even seemed embarrassed by the name, Celtic Tiger. G’won with ya.

The years of the Celtic Tiger, early 2000s to early 2010s, had been the first modern boom in Ireland. Consensus among the Irish remained that it had been a terrible business. Real estate prices had rocketed up. Then had come the inevitable bust. The banks had done a shocking business of swindling the Irish people who were now saddled with enormous debts from a government bailout of those banks.

(To recap: I had moved to Ireland with my family to open the EMEA HQ for Slack. I was trying to get to know Ireland and its business culture. We had to operate within that culture and hire people to fuel our expansion. I was trying to learn about Ireland while trying to operate in Ireland.)

The general Irish distrust of its own past growth and wealth seemed to loom over all of my initial conversations, as if the wealth needed to be watched. It was suspicious. Not to be trusted. Some chancer: here today, gone tomorrow.

I came to feel like something from the nation’s deep Catholic past informed this suspicion of wealth in an opaque way that was inconsistent with daily life. As far as I could see, money had been good for the Irish. Money was pursued with some glee and it created a tension I observed as both enthusiastic and shameful to folks. Sure, hustle. Fill your boots. But it might all crash down some day and don’t forget your roots. Let’s have a pint.

To help understand the Irish business context I read a few things, including Micheal Lewis on the Celtic Tiger days of the early 2000s and the consequences of the 2008 global financial collapse.

“Even in an era when capitalists went out of their way to destroy capitalism, the Irish bankers set some kind of record for destruction…Left alone in a dark room with a pile of money, the Irish decided what they really wanted to do with it was to buy Ireland. From one another.”

That article led me to questions about the Irish love for their land. Land ownership took on an almost mythic quality, largely, I learned, because it had been historically unavailable under British rule. I read the Irish play, The Field, and felt the history of the place in a new way. The tyranny of not owning their land shadowed and informed the living memory of the people I knew.

But where the Celtic Tiger and global financial crisis had been driven by credit and a circular real estate scheme, these new boom times, if you could get the Irish to agree that we were once more in boom times, seemed driven by San Francisco, New York, and the EMEA HQs for the invading US-based tech companies. In short, it was companies like Slack and people like me driving the boom.

In 2011 Michael Lewis had written:

Everywhere you turn you see both emulation of the English and a desire, sometimes desperate, for distinction. The Irish insistence on their Irishness—their conceit that they’re more devoted to their homeland than the typical citizen of the world is—has an element of bluster about it, from top to bottom. At the top are the many very rich Irish people who emit noisy patriotic sounds but arrange officially to live elsewhere so they don’t have to pay tax in Ireland; at the bottom, the waves of emigration that define Irish history. The Irish people and their country are like lovers whose passion is heightened by their suspicion that they will probably wind up leaving each other. Their loud patriotism is a cargo ship for their doubt.

Except. I found Micheal Lewis’ Ireland of 2011 bust times did not seem consistent with the Ireland we moved to in March, 2015. Something new was happening.

Flipping the Irish Diaspora

Instead of emigrating, now the Irish were returning to Ireland, along with everyone else who could. Sure the rich still lived abroad and dodged taxes from Spain or Luxembourg or Malta. And sure the patriotic bluster could get ramped up at times for Team Ireland. But it all seemed to have matured — less noisy and more substantive.

For the Irish I met, it seemed that this boom — if that was what we were in the middle of experiencing, no one could be sure, look, it could be a boom but please don’t use that word — it was different. More enduring and less saddling than the Celtic Tiger, and certainly not embarrassing. This was good work. There were solid jobs to be had. Could it be real? It seemed like it would be.

Immigration into Ireland was roaring. Housing stocks were scarce with long lines to see any reasonable flat available for rent. Into Dublin streamed the young and digitally mobile of the world — Brazilians, Swedes, Spanish, Germans. Even the English. The Irish diaspora flipped and Dublin became a magnet for the world’s digital nomads.

In Slack’s own Dublin office our first ten employees included two Canadians, two Brits, a Greek, a Brazilian and a balance of Irish. The Irish folks came occasionally from Dublin, but mostly from beyond — Meath, Wicklow, Galway, Louth. They knew each others’ home counties and all that each of them represented — agriculture, poverty, university, knife crime, horses.

And they knew each others’ accents too: Cork, Limerick, Donegal. They knew the hidden assumptions behind being from Navan, from Naas, from Cashel, whether they had ever visited those places or not. They knew the catholic university (University College Dublin) from the protestant university (Trinity College).

In short, the Irish knew the Irish, and all the hidden nuances of the culture that were slowly emerging to me. They knew that if you were young and bright enough, you collected your leaving cert and headed to college and likely never returned to your home county to live. Just for holidays and weddings. You could be upwardly mobile, so long as you didn’t have notions.

And Dublin pulled in the people because there was real business being done in well paying jobs — real employers paying real euros for services and products to be delivered. Sure, if you followed the chain of money far enough in a macro context it led to US-based venture funding and very low persistent interest rates seeking returns. But it also led to real businesses generating real revenues. It led to Slack.

I heard over and over as I landed and learned about Dublin that ten to twenty percent of the working population of the city was employed in tech. I looked at the directories of occupants on the office buildings and it struck me as truthful. This was the world we were joining.

Dublin Lives and Levies

Our short street in Dublin ran for about 20 homes, each brick row house similar to every other one. A house a few along from us had sold in 2007 for just under one-million euros. The same house sold again 5 years later in 2012 for €595,000. In 2016 it listed for sale again for €1.1-million.

The house we rented in Ranelagh was owned by Allen, who we never met. He lived in New York and was an expat Irish. Prior to our occupancy he’d rented the house to another family who had landed in Dublin to work at a US-based tech company. We inherited their iron, their ironing board and a few pots and pans in the larder. We followed in their footsteps, ensconced in the neighbourhood to work for a set period.

But that’s not to say that all was sunny skies for the Irish economy. The hangover from the Celtic Tiger days persisted in large but muted ways that hit people every day, yet didn’t particularly cause much fuss.

Since the corporate tax rate was 12%, and everyone knew this was a key contributor to the reason US-based companies were in Ireland, the money had to come from somewhere to fund government. As a result, personal tax was close to 50%, and varied very little based on income. Everyone got a significant haircut on their pay packet, sure, but it also seemed like everyone was in it together.

Taxes in Ireland were collected at source by the faceless entity known simply as Revenue, a clue to their straightforward role in the lives of people. No one filed a tax return unless they were wealthy or had professional help or wanted to dispute something. Taxes simply got deducted from your pay at source and your annual statement sent to you each year. Case closed.

Part of this automated approach felt refreshing — why not simply default to the mode that functioned for most people instead of forcing baroque spreadsheet and form filling gymnastics with tax returns and panicked deadlines? And part of this felt quietly tyrannical — the opacity of the deductions fostering a learned helplessness in the general population.

I also got the sense people felt like their taxes were a bit like complaining about the weather — a useless waste of breath that could unite folks in misery, but why bother? What could be changed?

Playground Conversations

We met folks in our Dublin neighbourhood and it certainly seemed like boom times had returned. At the playground with my son I struck up conversations that led to friendships and new wrinkles to the Irish story.

Niall worked in finance for a large construction company operating in 27 countries from their headquarters in Dublin. Serena led a sales team at Google and had been promoted 3 times in the past 2 years to keep up with growth. Eva ran the brand new Dublin-based innovation lab at one of the big 4 global accounting consultancies. Carl worked in infrastructure engineering for LinkedIn and was moving to Facebook after being headhunted. Geraldine led marketing for a series of top US-based, venture-backed software companies and flew to SF every few weeks.

My playground connections did provide excellent friendships, but didn’t provide me a representative cross section of Dublin or Ireland. My teammates at Slack provided a different cross section, with more diversity, but still it felt like being on the outside of a home, peering in through the windows to get a sense of the place, when really I wanted to open the door and step inside. The nuances eluded me.

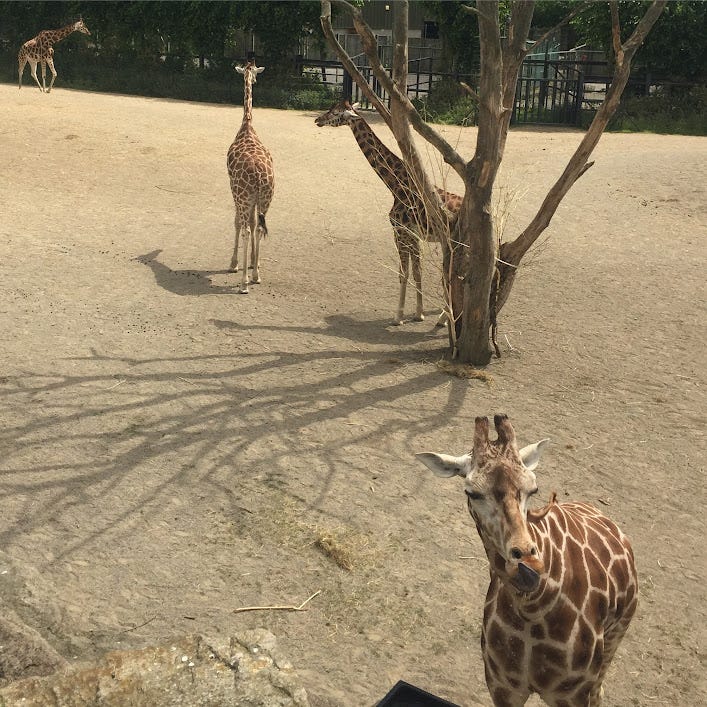

I mentioned in the last post how we ranged further as we got to know Dublin, and took the double decker bus across town to the Dublin Zoo one day. We saw where the Easter rising and Irish revolution had started almost a hundred years past, and where we now saw the people of the city on their commutes, running errands, meeting friends. Along tree-lined streets we travelled, watching the pharmacies, the take-away shops, the express grocery stores, the past never far away, consistently seeking to be heard.

Only occasionally between buildings at broad intersections did we catch sight of the run down, disappearing destitution of the north side. We glimpsed monolithic apartment blocks with broken windows that looked empty, or like they should be. Vacant lots littered with twisted metal. The bus chugged on, leaving us only snapshots of blackened skeletons of burned out cars.

Poverty and crime and desperation lingered behind the pretty streets and ornate, imposing churches. Dublin felt deeply like a place in transition whose past still lived off the tourists routes, whose past was not far behind, but whose tidal future was rushing in daily.

Up next — Culture Carriers: Doing the job in Dublin. Starting with Hanni. Finding a fridge. Fitting into life.

No tax returns 🤯

We just finished the first season of The House of Guinness, which is a historical drama set in 1860s Dublin. It’s very good and seems to capture that period, not long after the famine.

It’s created and written by Steven Knight, who wrote Peaky Blinders (a favorite) and has a similar feel.