Just Like Starting Over

Launching in Dublin. What is Slack, again? Telling our story from scratch. Flying to find the complexities of Europe.

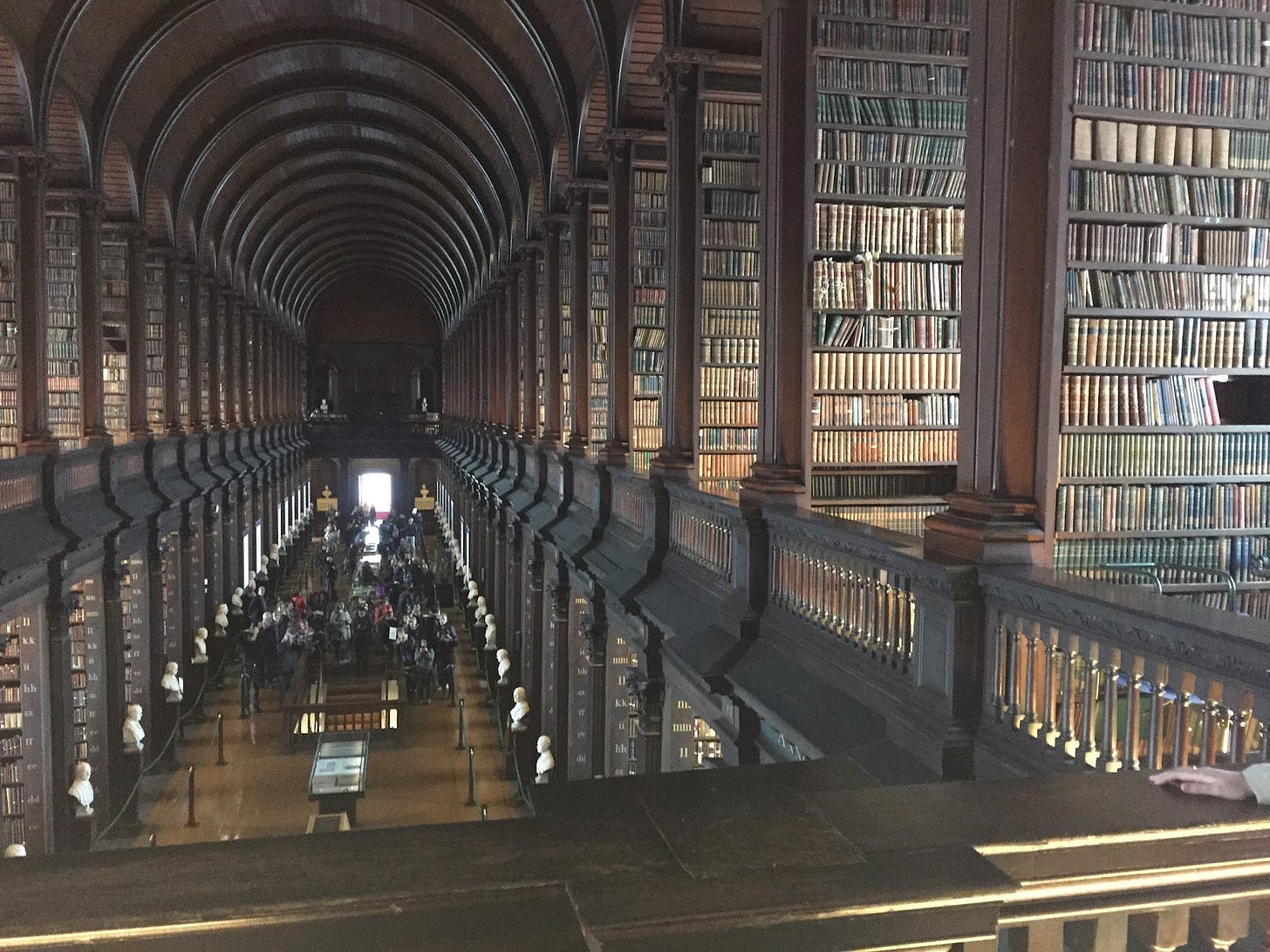

I remember standing in the Long Room of Trinity College Dublin with awe. It was the most magnificent library I had ever visited, two levels of bookshelves, dark wood and leaning spines, tapering into the far distance like some unbounded grid of bound human knowledge.

The ushers cleared out the crowds of tourists. The hum of voices faded with their echoes so we were left alone in the silence for our photo from the balcony, the full scale of the location as the backdrop. We posed for our official photo.

Launching Slack Dublin

We “launched” in Dublin with a fairly high profile event on May 14, 2015. (I say “launched” because we’d already been operating for many weeks and we held the event for public relations purposes.)

Our PR team and the IDA Ireland team marshalled their collective might and landed the Taoiseach, Edna Kenny, the Prime Minister and head of government of Ireland. They closed the Trinity College library for an afternoon for a ceremony and our photos. It was a big splash.

The signals of the event showed me a few things about what I could expect working in Ireland. It was a gorgeous place full of a proud history and fine traditions. It was large enough that folks knew it, yet small enough that a company of fewer than 5 employees at the time might nab the country’s leader for a photo opportunity. Symbolism could do a lot of work here to tell a story. Our story.

We met the government officials and chatted amiably. Their handlers were in charge and choreographed us. In the small moments as we waited Mr Kenny asked me how we were getting on in Dublin and whether I played golf. When I said I did not play golf he replied that “a lot of business gets done on the course so you might want to be taking it up.”

Once we got to the official questions from reporters, they remained: And how many employees have you got? And how many will you be hiring? And what kinds of jobs will those be that you’re opening?

Team Ireland proved very serious about employing as many Irish people as possible. And our role as a foreign direct investor in Ireland was clear: hire people. Pay them and train them and advance them and grow to hire more people and dear god keep them all employed. Now go on with ya.

Telling our story: PR

One facet that had fuelled our success in building Slack to this point was that people knew us. Our PR game was strong. We came from the communities we had been trying to reach, so our initial outreach and story had been to folks we knew and related to — tech nerds knew us because we were for the most part tech nerds. Then as we expanded we needed to tell our story more broadly to a more general audience through the media.

And being perceived as cool and new and different in a business context helped. Our weirdness helped. Our counterintuitive name helped. Our story of the plucky team with the failed video game who had failed before with a video game and turned it into an inventive and important company named Flickr definitely helped. People could cognitively jump ahead and feel clever for knowing how this story would end too.

For lack of a better word, we had pretty strong status among the tech startup geek communities and we’d been able to expand a similar strong status in more general circles.

But arriving in Dublin it became clear that the European tech startup geek community was smaller and less influential than on the west coast of North America. The mainstream media was mainstream, covering the economy, crime, politics, real estate, government and existing large industries. They majored in opinions. They were far less interested in the new new things from the tech industry, and far less oriented towards Silicon Valley and tech success stories.

A few small blogs existed to cover the tech startup geek community but they didn’t have the same reach or credibility. No one at the Irish Times or RTE covered startups in the same way that the NYTimes or CNN covered startups.

Learning to Tell Our Story Again

When I introduced myself in SF and said I worked at Slack people almost always knew Slack. Same in New York. Mostly the same in Vancouver. But as I traveled further from the Silicon Valley centre of the tech world, the recognition of Slack grew fainter as the signal faded.

When I introduced myself in Dublin and told someone I worked at Slack I also needed to answer the unspoken question, “And what is Slack, again?” The key parts to our story that people were interested in were not how we were cool or different or weird or reinventing work. No one really cared much about our failed video game past.

The key proved to be more tangible and patriotic to the home cause in Ireland. How many people were we employing? How many did we plan on hiring? It was employment that mattered to them and the number of people in our plans that got their attention.

For context, Google had over 3,500 employees in Dublin. Facebook had over 2,000. LinkedIn was approaching 1,800. Dozens, perhaps even hundreds of other US-based tech companies had a few hundred employees.

Tech was a very big industry in Dublin and growing incredibly quickly, but my sense was that locals still felt it was a bit flighty. The Irish had been charmed by an economic wonderstory before and would not be so fooled again. To really matter, we had to translate our story into growth plans focused on the number of people we planned to hire. So we did. We transitioned from focusing our story on us and our journey to focusing on our employees, current and future.

And that expansion path was well established. Here’s a rough outline of how it went:

Get your landing team set up and Culture Carries and your initial hires in place for your first office.

Grow to 20 or 30 people in Customer Service and Sales and fill that first office.

Get a new office to grow to about 120 people.

Add to your Customer Service and Sales teams with representative business services in Accounting and Finance, Human Resources and Recruiting, IT and Technology Operations.

Start to create focused teams based on market groupings – UK and Ireland, Benelux, DACH – with market and language experts.

Start building out satellite EMEA offices in London, Paris, Germany.

Through this crash course in global economics, I learned about market sizing for global software sales. The US was the #1 market by far, with the UK, Germany, Japan and France each around 5 percent and then a host of countries such as Canada, Brazil, Spain, Italy and Korea with a small footprint but no significant size. China was absent from our plans because they were China.

I also learned that though Europe seemed like a large market, comparable in size to North America, it was actually much more accurately described as 27 small markets with a single currency and 24 languages, and then the UK.

In seeing the complexities of Europe I also started to recognize the huge built-in advantage US-based startups had in their home market: one language, one country, one currency, one overarching narrative focused on technology advancement and success. To be able to target the largest market right in our own backyard gave Slack a huge head start. Sure the business culture of New Orleans differed from Seattle and Los Angeles from Charlotte, but everyone knew the NFL and had the same president and recognized the New York Times and Wall Street Journal.

Pockets of Believers

As we started to adapt our story to Europe, we found a very close relationship between how open, global and digital a culture proved to be and how quickly they embraced Slack. Sweden had pockets of advanced companies using Slack. Lithuanians used Slack. Software developers in Russia used Slack. Digital marketers in the UK loved Slack. In our conversations in those markets doors were wide open already and they believed. We didn’t have to start from scratch.

Outside of those markets, we needed to knock hard on doors to get an answer. Bankers in Spain and France and Germany were curious and could perhaps see using Slack, but mostly in their innovation lab where they played with toys. Bankers at Barclay’s in London were already using Slack, though unofficially. It also felt like receptiveness to Slack was a light switch — either on or off, with very little intermediate dimmer setting.

To add to the overall market complexity in Europe, the mix of company sizes in the general economy was different. More small companies existed than in the US, but they generally didn’t buy much software. They had been around for a long time and tended to be family run. Conservatism dominated their decision making. So we looked for pockets we could sell to, often with a new generation taking over.

I flew to Paris to meet with the Chief Digital Officer of LVMH, an America who Stewart introduced me to, describing my “honking French” as good enough to get by with. Thankfully, we met in English and I didn’t have to parlez vous.

Their offices were exactly as subtlely lovely and quiet as you’d expect, above the chic shopping streets and establishment hotels. They used Slack in their digital teams but getting the rest of the organization to use it? Yes, a great idea. Certainly better than email. And yet…(much shrugging). C’est difficile.

I flew to Berlin for a 2-day IT conference to stand at a booth in a conference room one day and present for 45 minutes on collaboration the next day. The booth work was fine. We had banners and a screen and some folks had heard of Slack and I could demo the product live for them on the screen. That demo also attracted others to learn more. I met some live Slack users in the room. They had very specific technical and administrative questions that I could answer, and it felt rewarding to so, and it showed others standing around that we had a real product with actual users.

The big event though was presenting for 45 minutes to IT managers. How could I make that not boring to a room of 50 people who felt they had to attend because collaboration was in their job description, but really they’d prefer to just manage the IT application settings and leave people out of it. PEBCAK was an acronym I’d heard and that came to mind with this audience: Problem Exists Between Chair And Keyboard.

So I made the presentation and workshop about their problems communicating. What were their problems? How could they get people to follow instructions? How could they know if their work had any impact on the folks in their organization in Finance or Project Management or on the front lines working with customers?

Surprise! They were not keen on a sales presentation and very keen to talk about their own issues. And surprise again, it turned out many of their issues were at their root reciprocal communication problems. We voted on the top problems. I showed them how to solve them in a hypothetical world where they used Slack.

It felt a bit like a high wire act, reminding me of those early calls with Stewart where we’d demo live our private, internal Slack workspace to prospective customers. But it got them nodding and thinking that a better world could be possible. Their life didn’t have to be a sequence of ignored emails stacked upon each other all the way down.

Complexities of Europe

I flew to Frankfurt and learned about the German mittelstand, a group of family-owned companies of fewer than 5,000 employees that made up the backbone of the German economy. They prized enduring through change and turbulence.

The German mittlestand companies provided a very good test for us to learn how to sell Slack to skeptics, but skeptics who could be reasoned with and were open to new methods and technology that made sense. We sold to metallurgic engineering firms with cutting-edge factories. We sold to 18 divisions of Bosch that each had their own decision making process and budgets. We sold to Volkswagen’s trucks division.

The overall experience felt both like a flashback and like a present moment. The flashback was to our early days, introducing Slack and getting those first few conversations started: here’s what it could do for you. Sometimes those conversations led to some traction, often times they led to some polite deflections.

The present moments happened when we connected with pockets of tech progressivism trying to push ahead among so much general static anxiety, or maybe just so much indifference. Everywhere we met people we found people trying to reinvent and improve how their organizations communicated. Slack as a product held promise for them and our job often amounted to arming them for internal arguments to create change. We had to help them build their own case.

Upon an invitation from one of the big 4 accounting firms, I flew from Dublin to London for a day trip to present Slack to one of their clients. The client was very secretive. The division of the big 4 accounting firm was their digital consultancy. The division of the big 4 accounting firm were using Slack. But they weren’t technically allowed to use Slack. So they said it was just a trial.

When we arrived at their offices — glass-walled, blonde wood tones, a fashionable street address — we learned the client was the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, an organization started in 1099. Kind of a country, but not really. They had no land but could issue passports, stamps, coins and licence plates. They sat as observers on the General Assembly of the United Nations. They had diplomatic relations with 112 countries. I wondered as I prepared: what kind of Da Vinci code were we into here?

With some scarce information we did our best to show a compelling story for the Order. We presented and everyone treated us very politely. We got questions about how Slack integrated with email. But there was zero chance they were going any further with Slack.

After our departure in a delightful pub patio under shady trees I debriefed with my teammate Paul. We’d been called in to present, but it was clear we had no chance at any deal. What had just happened there?

We came to the realization that we were option number 3, called in for a bake off to make the Big 4 accounting firm look good and innovative and in touch with new technology, and to be an easy No for the client making the technology decision. Okay then.

Lessons learned: pre-qualify presentation opportunities and be willing to say no, nicely. Get to know the customer well before committing time and attention to travel and present. Don’t work through intermediaries who control the customer relationship because a generic presentation to a indistinct customers didn’t work.

The presentation to the Sovereign Military Order of Malta stands out for me because it reflects the general business culture we ran into in Europe. On balance, there was a desire to try new things. There was curiosity and a currency in being current.

But getting going was hard. Adherence to the past way of doing things was crippling. Sure there was an interest in staying in touch with technology and an understanding of how it could drive the innovation, productivity and attractiveness to employees for their firms. But change felt very hard and carried risk. And it wasn’t really anyone’s job. And it wasn’t what they knew themselves as capable of.

In some places in Europe receptiveness to software was even hostile. Why would I want something where my employees can communicate with me? Can interrupt me? Can get me at any time they want on my mobile? And searching for something? I don’t do that today. Why would I need to do it in the future?

One tactic we did start to use was more relational — asking if our prospective customers used text messaging (of course they did, it’s great) and news alerts (well yes, I need to know what’s happening) and then positioning Slack as a combination of the two, but for the teammates they trusted and organization where they worked. This had some resonance and made our proposition more palatable, less strange.

And once again we were reminded of the MAYA principle — Most Advanced Yet Acceptable. But in Europe we needed to pretty drastically recalibrate what Most Advanced meant so we could even get to a discussion on what might be Yet Acceptable. It felt very much like we needed to take one step backward to take two steps forward. We flailed about for some time in the examples above and beyond before we really found our footing.

And so we came to key moments and our sales numbers were okay but not great. Compared to the North American sales numbers, our growth was slower and starting from a smaller number. It felt frustrating and underwhelming.

All our conversations internally stayed positive about our expansion to EMEA. Sure, we had to do it. It was where growth would come from, eventually. But it was hard to be running a market firmly in second place by both size and growth rate to our teammates in North America.

How could we change that leader board? And how could we hire folks with expertise to help change that leader board? Good questions! Those would prove to be the next challenges to face.

PS: I can’t resist telling just one more story.

After we did the PR work of launching Slack at Trinity’s Long Room library, we had a small celebration for the team. But first, walking to that celebration, I had a job to do: interview Ciaran Chaney as a candidate to join Slack as our Office Manager.

Ciaran was familiar to us because he’d worked at IDA Ireland to help Slack set up in Ireland. He’d been interviewed already by our facilities team in SF and they’d given his candidacy the green light. My conversation with him acted as a final check on how he’d fit in as a Culture Carrier.

We wound through the narrow sidewalks of Dublin’s tangled streets, fighting for space with pedestrians and cyclists. We talked about his career, where he wanted to go, what mattered to him, what we might have conflict about, how he dealt with conflict. Ciaran was in the lead because he knew his Dublin directions. He told me stories over his shoulder to keep up the pretence of a conversation without running into anyone. We ducked and wove between umbrellas as it started the daily rain.

We arrived at The Long Hall, perhaps the greatest of Dublin’s thousands of pubs. The interview ended, and we went in to celebrate. Ciaran joined Slack as soon as he could thereafter and became a stellar, confidence-inspiring and essential fixture on the team.

But Ciaran’s hiring at Slack wasn’t our typical hiring process. Usually we worked more rigourously, more in an office context, less in a sidewalks setting. And we had to work quickly if we were going to meet our own expectations.

Up next — Hiring Good Irish Hybrids: Hiring all the time. Selling Slack to candidates. Adapting Slack to Ireland. Guessing that it’s a little from column A, a little from column B.