Leaving Never Neverland

Growing up and growing apart. Finding our competency traps. Matching our customers. Becoming Sales.

Growth at Slack led to new problems. Some had good answers, like adding more people and adding more expertise. Some created more tension and lingered, like a pebble in our shoe, because as we grew, we also maybe had to grow up, but also didn’t know how.

Maybe we had to grow up? Okay, definitely. Eventually. At some point.

At first, I confess, I felt pretty hesitant to accept that we needed to grow up. What did growing up mean? Two big things right away: external leadership with more experience and what they could bring — a more conventional business-to-business software selling approach.

I dawdled and dragged my skeptical heels. Hadn’t we done pretty well so far? Shouldn’t we keep tailoring our work to our product and market? Learning as we went? Inventing what we needed? Instead of adopting the conventions of the industry? Was it maybe me that was stuck in a Peter Pan world and not wanting to grow up? Maybe, maybe?

Okay, yes. We needed to grow up and move up market into larger deals. Our customers were pulling us there and we needed to scale our sales organization. We needed folks who had done this thing before and learned the lessons, and I was scared of what that might mean. I kept reminding myself of the classic I’ve mentioned a few times lately: good decisions come from experience and experience comes from poor decisions.

So I had to get out of our way. We needed to bring in some experience because we didn’t have time or latitude to make the poor decisions and gain our own experience. When faced with 10 options of what to do, we needed folks who could point to the leading 2 or 3, and then help us decide between them.

We needed to recognize that what got us here wouldn’t get us where we wanted to go.

Growing Up and Growing Apart

Just as we hadn’t reinvented Accounting or Recruitment or IT to suit our needs, we needed to remember we didn’t need to reinvent Sales to suit our needs. Even if we had started out believing we wanted to reinvent it. Many large B2B software companies, like we hoped to become, had already been built, and they pretty much all looked the same.

If we aspired to follow their path (and we did) then we needed some shortcuts. We just had to get over ourselves and our own success to see the lessons we needed to learn. (That last sentence might as well read, I just had to get over myself and my own modest success. The things we had built and that had worked so far could also constrain us in the future.)

So we did what all technology companies did to make a decision. We called an offsite. It felt about right timing wise anyway. We had kept hiring at a quick pace and we needed to anticipate that our pace would only increase as we kept succeeding. New people meant new ways of doing things. Change was coming and coming fast. We were ~20 people and going to be double that and double that and double that again soon enough.

As we readied for the offsite we scoped out what we wanted to achieve. AJ and I spent time on calls building agendas. What did we need to do?

Get the team together. Actually see everyone in one place for the first time. We needed to humanize everyone.

Introduce new team members. So many had never connected with each other. We needed to create bonds.

Figure out our mission as a team. Get some words to describe ourselves and our mission. We all needed to pull in the same direction together.

And lastly, answer the biggest elephant in the room question: were we an Accounts team or were we Sales? We needed to decide on an identity.

The question of whether we were Accounts or Sales felt important at the time. AJ and I had batted the question back and forth. He came from a Sales background. I came from a no-Sales background and feared what going all in on Sales could mean: finger guns, jumping on calls, cutthroat quotas and stack-ranked leader boards.

Looking back (and perhaps looking in from an external perspective) it seems like such a fine detail to focus on. What a trivial bit of precious self indulgence — Sales vs Accounts! But the question of our team name also acted as a signal of an internal question we struggled with about our purpose. Did we exist to help customers use the product and maybe do some commercial business? Or did we exist to do some commercial business and help customers use the product?

And perhaps you read that last sentence and thought, what’s the difference? Get over yourselves and get on with it. It can’t matter that much. And I get it. It is a bit of Silicon Valley myopia. A foamy latté problem (“My la-tay is too fo-may.”).

But I’d defend the question of Accounts vs Sales as a moment of navel gazing that actual led to better team work, simpler hiring and clearer internal incentive systems. It helped us answer key questions. For example:

Do you move to an industry-standard variable compensation system that rewarded deals? If so, how do you balance base salary versus variable compensation?

What roles do you need to create on the team to reflect your team purpose?

How do folks get reviewed and promoted? How do we hire? Who do we hire?

All those questions hinged on our purpose as a team and the team name reflected our purpose.

So, all this to say, at the time the name of our team did feel important. Important enough that it got its own session in the offsite and still sticks with me as the most vivid question we had to answer. It held all the tension leading up to the event.

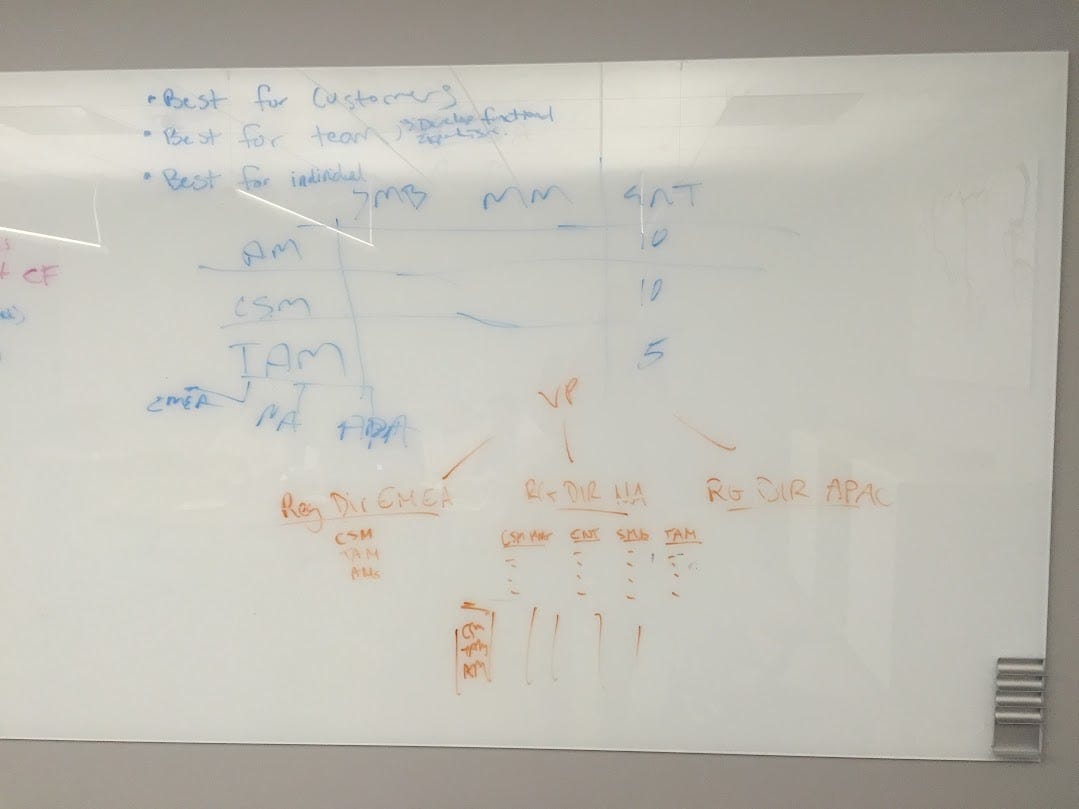

And that tension reflected our team’s evolution. As we’d grown and added people to the team in North America, we’d already started to add new roles. At the start, the Accounts team consisted entirely of Account Managers responsible for all the questions that any customer that walked in the door could have. All Account Managers acted as a single point of contact for the customer to answer all their questions. But then we couldn’t answer all their questions. We had found our own competency trap.

Competency Traps

As our deal opportunities and customers got bigger and more complex, our “everyone is an Account Manager” model started to show some cracks. We had gotten very good at working with tech teams inside larger organizations, and with smaller and mid-sized technically-minded organizations.

And our Account Managers were instrumental in this success. Customers really liked to have one point of contact to help answer their questions. Our Account Managers liked to be experts and to be able to marshall their portfolio of skills to answer those diverse questions and be the single point of contact. It worked.

But in larger organizations, we struggled to succeed as much as we could. And with more traditional organizations, we struggled to expand beyond tech teams. Our Account Manager generalists were pulled in too many directions. Our customers grew more complex, more conservative, more passive about solving their own problems or even asking about them.

Plus, the supply of Account Managers felt very thin. Finding successful candidates with the range of skills and experience necessary to fill the role proved challenging. Customers loved to have one point of contact. But we were learning we couldn’t train that single point of contact to be an expert on everything. We had reached the limits of the model.

Matching Our Customers

What we needed to see is how we needed to start to match our customers in all the ways they expected. We needed to bring in mid-career and senior folks to sell to larger customers and to sell more complex deals. Okay, right then. So what did that mean?

Those mid-career and senior folks were used to living in a larger Sales organization, supported by many specialists. They had titles like Account Executive. They had territories and industry expertise and quotas and contacts and travel allowances that fed into travel rewards programs they used for their personal vacations. When we interviewed one of these folks it felt very different, like we had moved from the junior school playground to the senior school locker room. This was a new game. We didn’t know the new game well, but we still found ourselves playing it.

The first additional role we hired was Solution Engineer for deeper technical expertise. Kevin Albers joined the team and got to work on the implementation details for Slack, like security questionnaires, Single Sign On (SSO), authentication and API integrations. Our demos for customers started to include Kevin riding shotgun to handle the technical details. Customers liked that. It matched what they expected. And it proved handy that Kevin’s expertise on the calls accelerated deals for our larger customers. Yes, please. I could see perfectly how that was a winner.

Customers got bigger and calls also got bigger. Customers often brought along their Technical Architect or Engineering Director or Security Engineer to ask technical questions. We had Kevin. He was an ace at answering questions and we reached his capacity pretty quickly, so we added two more terrific Solution Engineers: Britt Jamison and Karishma Kothari. But we still needed more to match our customers.

To help with successful adoption of Slack and expansion of use, a whole domain of expertise existed called Customer Success. We had been helping customers as Account Managers. Now we needed to level up. Rav Dhaliwal joined from London and taught us what Customer Success meant, supporting customers with things like rollout plans and quarterly business reviews. Hot damn, those acted as catnip to hesitant fence sitters and skeptics, even before they had them. Just the promise of them painted a vivid picture of what success could look like for a customer. Helping them imagine that future turned out to be something they wanted very much.

Sales Math

So we improved how we matched customers in explicit and process-oriented ways that they needed. Solution Engineers handled the technical implementation bits. Customer Success managed the organizational change. An Account Manager quarterbacked it all.

But then we started to see that we had also started matching customers’ implicit needs with something I started to call Sales Math. Everyone expected that each side on a call would have roughly the same number of contributors. Each contributor would have a role on the call, like in the cast of a play. Each contributor would have a kind of counterpart on the call.

If this symmetry didn’t exist, if the contributors to a call didn’t balance the Sales Math, the call more often than not, didn’t go well. We at Slack would get hit with questions or issues that needed to call on expertise not present. We hadn’t prepared well enough. The customer would need to wrangle their internal people to move things ahead. They weren’t ready to proceed.

Was that always true? Not always, no. But we almost always needed an equal number of people on the call as the customer. Sales Math showed that each side was dedicating equal resources to the call. Specific people could be prepared to tackle specific topics, whether they were contentious or just required some expertise.

When it went well, Sales Math meant if you were an Account Manager leading a call, you could sell your organizational strength and show the customer how important they were, how many people were dedicated to their business. You could also push some topics to specific people in a way that felt transparent. Get a tough question? Repeat it and ask one of your own people on the call if they have any idea. Punt it to follow up on as an action item. Let someone else be the person to say no nicely. Circle back on it later.

So yeah, Sales Math showed us how we had to mature our processes and team to match our customers’ expectations.

Becoming Sales at the Offsite

We landed in San Francisco from the overnight flight, ready to get cracking. A mini bus took us north to Sonoma with a full agenda and big ambitions. The fragrant air and warm temperatures and golden light felt lovely landing straight in from Dublin in damp December.

Four of us arrived — the full Slack EMEA team — to join the 15 or so folks from Slack SF and Vancouver. The last thing AJ and I had committed to in our preparation calls was simple and hard at once: be brave.

AJ and I led our first session setting up the offsite — what we wanted to accomplish and how we wanted to engage. Our agenda looked ambitious and a bit daunting, so first things first, let’s be brave: were we Accounts or Sales?

I remember everyone expected this to be a contentious discussion, fraught with hard questions and conflicting views on our purpose. But then it wasn’t. We all agreed in 5 minutes. The thing we were doing was selling so we let’s be Sales. Okay, done. Great! Decision made.

It felt like a weighted lifted, like we as the leaders had expected we’d have to really sell Sales to the group. We expected to swim into the current and the tide had flipped. We were Sales.

The rest of the agenda proceed well. The team photo above captures pretty well the feeling of that day. We were together. We knew who we were. It was time to go and show the world.

Up next — Meet the new, new, new boss: Feeling our teenage years. Finding a top-1 leader for growing Slack. Hiring our new boss.

The thing you thought was so uber important, so fraught with meaning, took 5 minutes to figure out. Of course. But I love the unpacking of the perceived importance after the fact.