Slack's Wall of Love

What I hear you saying, on Twitter. Reaching tech nerds. Listening then amplifying the best parts. Maximizing the surface area of the company.

In the beginning, we knew our people: tech nerds. To reach our people, we knew we had to do well on Twitter. After all, we were all tech nerds and we were all on Twitter. Our friends were on Twitter.

Twitter acted as the engine of discovery of most new things for our tribe, at the time. RIP that Twitter.

When Slack launched in 2014, Twitter collected the attention of tech nerds and parcelled it out in 140-character sips of adoration, ridicule, banality and consumption. And Twitter acted as a key external voice for Slack as we got started.

For example, we didn’t have a changelog of updates to our product to tell people what had been updated. We’d basically said no nicely to having one. We just posted on Twitter about the changes when they went live with the hashtag #changelog.

To see all the changes, we told our customers (and sometimes our internal employees too) to click on the #changelog link on Twitter. It felt like, shrug, the best we could do at the time. It also felt like we were developing the product partially in public, sharing the journey with our customers and collaborating lightly on the process.

So being good on Twitter with our customers acted as a game, and I’ve already made the case that the team at Slack loved games.

Playing the Twitter Game

The Twitter game required knowing the explicit rules and mechanisms of the platform as well as the implicit social context and pecking order of the people.

We had some experience with the platform and fluency with the people. Stewart was @stewart. Our CTO Cal Henderson was @iamcal. That fluency led to comfort with the game and that comfort led to playing well and building a following.

It also felt like it mattered to us to play the Twitter game well, like the Twitter game contributed to the tech startup game. It showed we knew our initial customers, and that what they valued — a combination of wit and substance, honesty and playfulness, maybe some absurdity — we also valued.

So we created the Twitter account @slackhq and started to play the game. Stewart and Ali Rayl, our leader for the customer service team, mainly handled the account and made the account popular and well loved with a mix of wit, candour and succinct sincerity.

In turns sometimes scheduled and sometimes impromptu, the Slack team traded off posting from @slackhq. Stewart posted occasionally and often in late night bursts. @slackhq made jokes, replied to inquiries, reposted noteworthy news and complimented people. Everyone who wrote to @slackhq got a reply. I never posted.

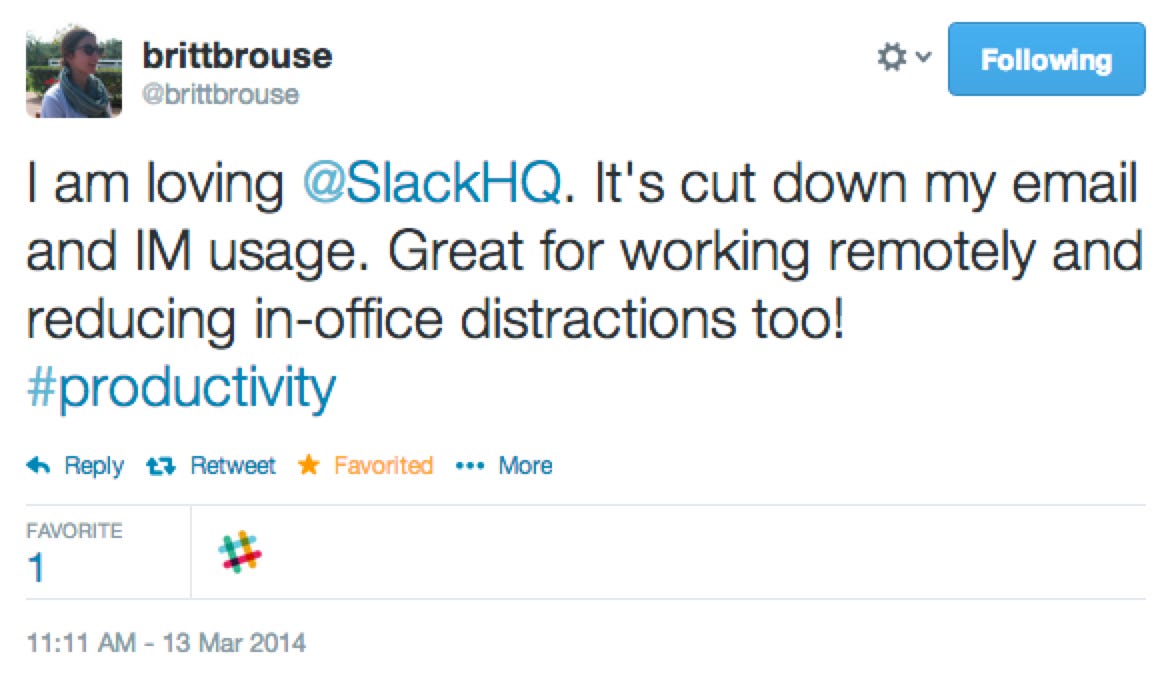

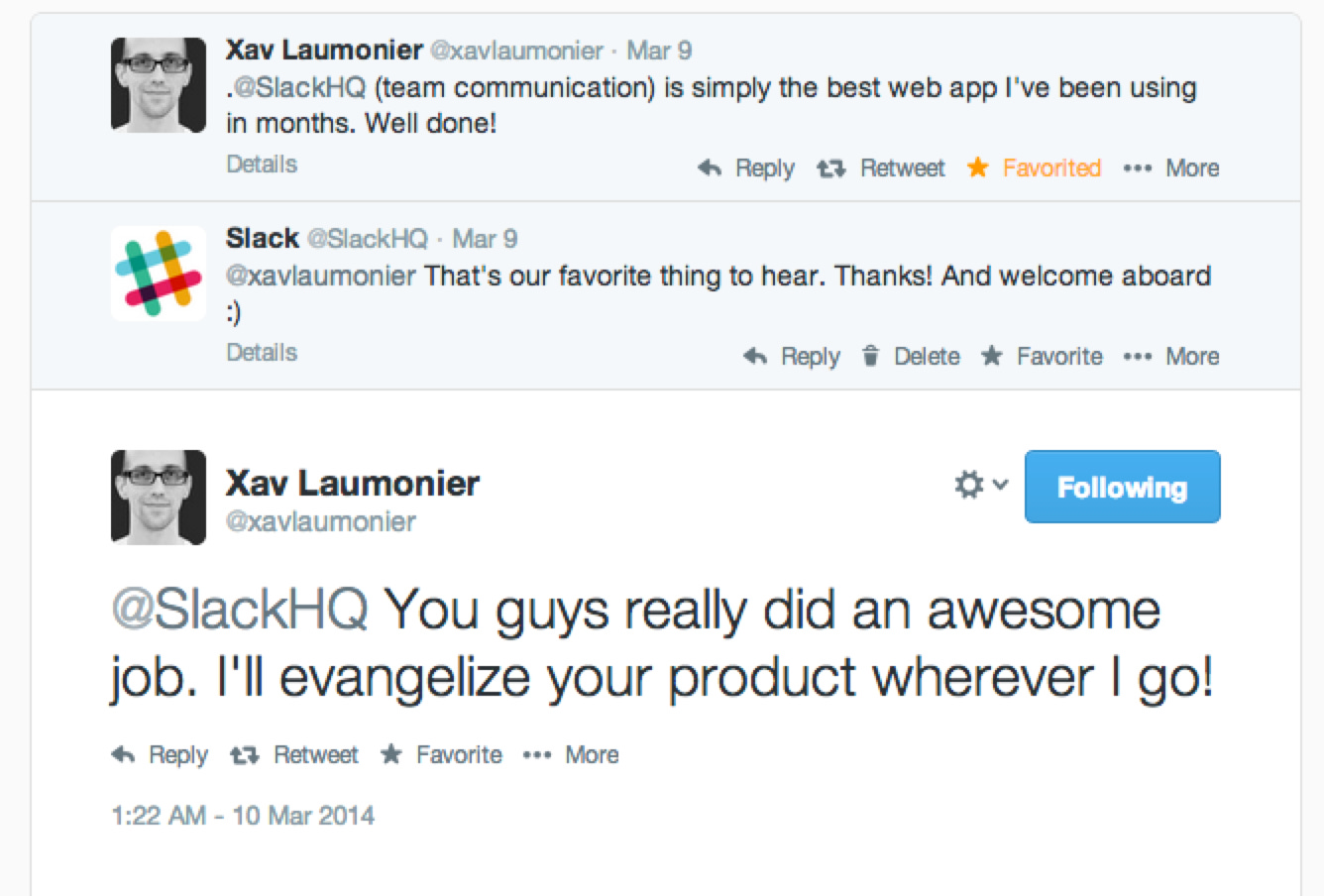

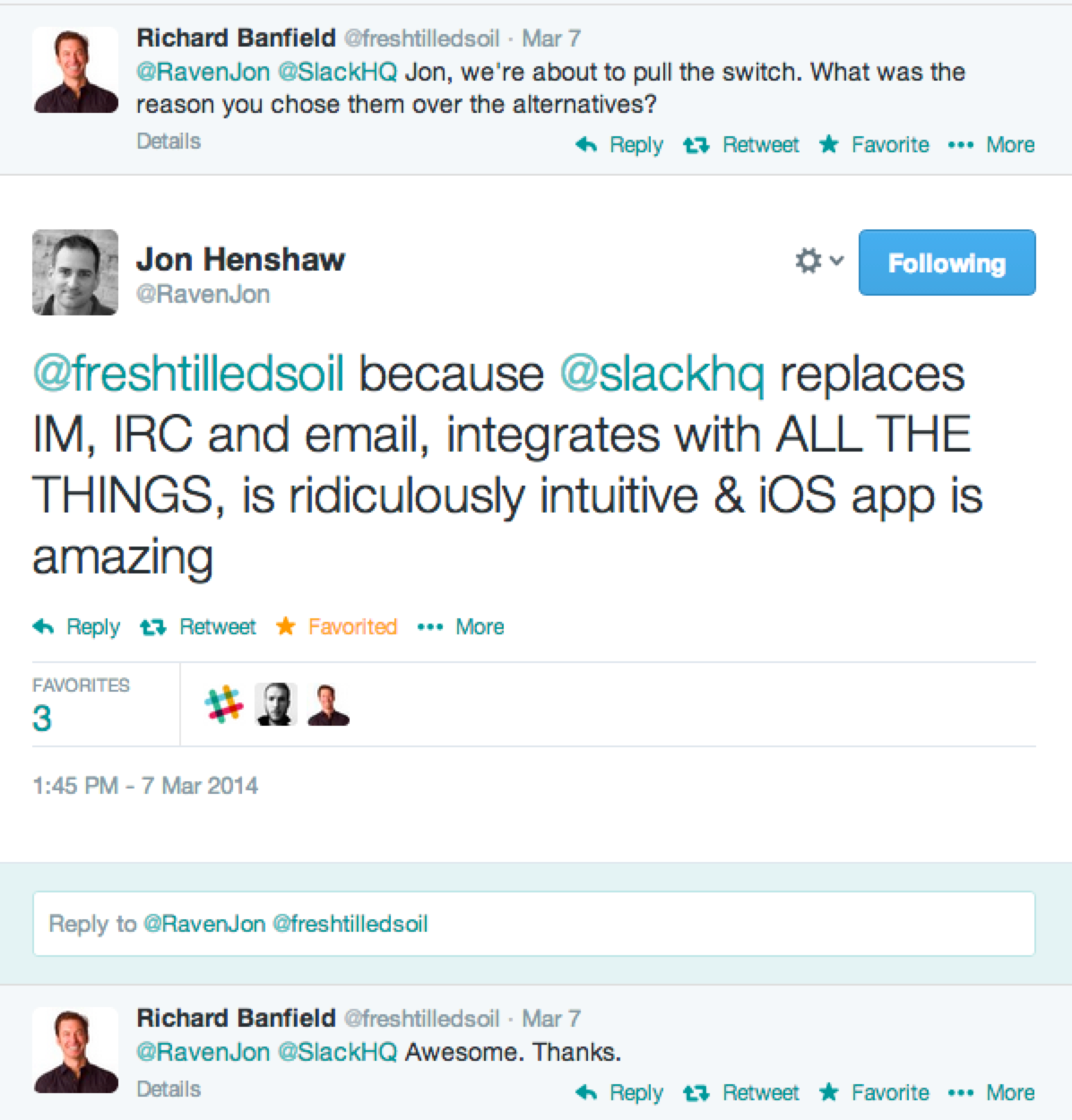

As @slackhq excelled at the Twitter game and as we launched Slack the product, folks began to reply and share their experiences as Slack users. This gave us a very strong pulse on the feedback of tech nerds responding to our product. It also gave us a terrific marketing opportunity that emerged as we watched.

We collected lots of really positive feedback on Slack from tech nerds on Twitter. But so what? How could we harness that feedback and share it with the world of doubters?

We had a sense that nothing would feel more undeniable to non believers or skeptics than unsolicited public declarations of support for Slack. Here were our customers reviewing our product and saying how great we were! Here was word of mouth made tangible and shareable. In another grubbier context these could be called testimonials or endorsements. So, I wondered, what could we do with these?

Creating Slack’s Wall of Love

To start, I kept a collection of effective tweets for combatting common objections with customers. I’d use them in email replies and call follow ups to reinforce a point or demonstrate what someone else had already found.

Too hard to start or change? Not sure of the value of trying it out? What will it be like to try? We had a tweet for each of these situations and many more that we could share to showcase someone else’s success already tackling that same issue.

And it worked well. The individual tweets proved effective at overcoming objections. Concurrently, more positive tweets kept coming in. The collective weight of evidence of them all started to seem untapped.

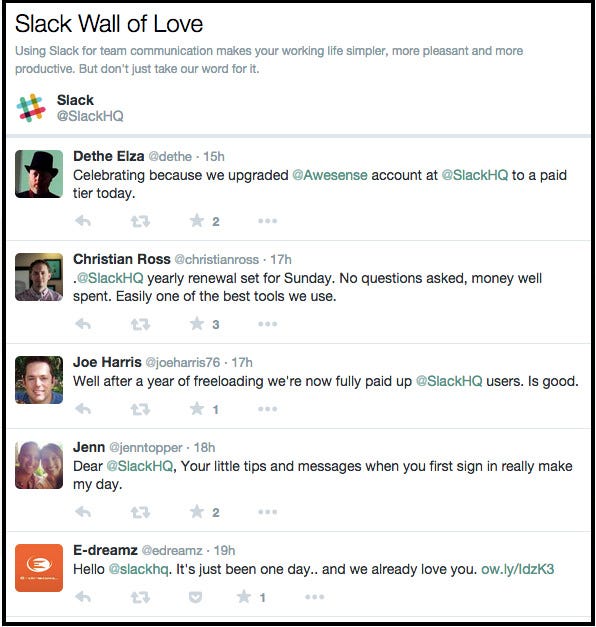

As that tweet-sharing success started to prove itself, I started to collect the positive tweets into a Twitter product called Collections. It let us have a page just comprised of our selected tweets. We called our collection the Wall of Love.

To see what that might have been like, read through the tweets below. You’ll likely get bored and skip or skim a few of them. That’s kind of the point. The evidence overwhelms in aggregate.

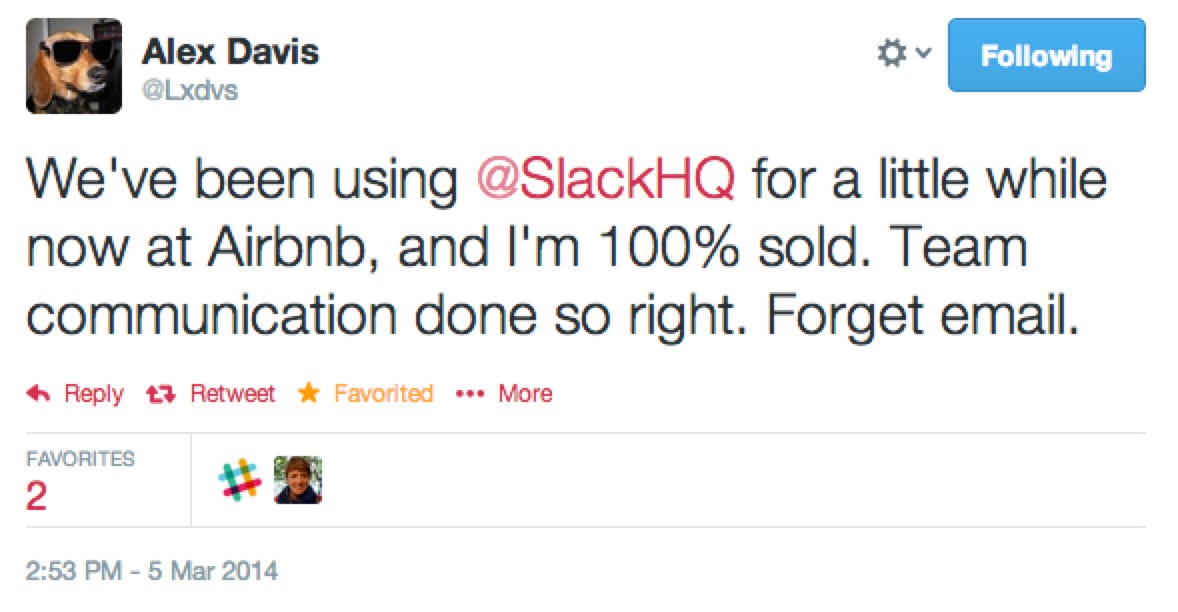

Collecting the tweets also gave us an authentic feel. For example, is it better to have an Airbnb logo on your front page or to have one of their leaders post this?

I’d argue it’s much better to have their design leader post the tweet above endorsing your product. It let our customers do a good portion of the selling for us.

Love Expansion Machine

Here is what the first version of the Wall of Love looked like.

When we started the Wall of Love we already knew the Collections product had been deprecated inside Twitter. It would received no support or development. It was End of Life, as they say in software.

But no matter its status, we used it. If they killed the product, we’d figure out an alternative. We were still a small team focused on saying no nicely to any opportunity outside our absolute core functions. That’s how we felt we had to work. But that didn’t mean we stayed static. We had a team working on tweets. Stewart sometimes shared one with me to use. I’d find many on my own. Other folks on the team would share them too.

I started the Wall of Love with a single curated list for sales conversations. Then it expanded to press inquiries, new employees, investors — anyone curious about Slack. When someone was skeptical about Slack and how it worked, or questioned how popular it was, or, or, or — we’d point them to the Wall of Love. Simple.

But pretty quickly because of the growing popularity of Slack, curating the list of tweets became an hour or two of work each day. After we had launched the paid Slack product, we started even more curated specific lists for:

Pricing — Is it worth it? Why should I pay? What value do customers get? How come it’s so expensive???

Productivity — Does Slack save time? Can I find anything? Does it improve teamwork? Will it work for our team?

Change — Will anyone use it? How long does it take to adopt? What if I want to cancel? What if no one uses it?

Competition — What about Slack vs Skype? vs HipChat? What about transitioning to Slack from email?

In addition to the benefit we got from having the Walls of Love external facing, we also piped the tweets into our internal Slack workspace so all Slack employees got to feel the love. And there was a lot of love.

Wall of Love 2.0 and @SlackLoveTweets

A year or so after launching Slack’s paid product, we kept growing and we hired more people. I stopped managing the Wall of Love and an expert stepped in.

The volume of tweets kept growing and it was hard to keep up and make what amounted to editorial decisions. What to include? What to omit?

The expert who joined was Matt Haughey. When I asked him about it, he said:

“I essentially joined Slack because of the Wall of Love. I saw it on the homepage when I was considering joining and it blew my mind. Here was a company that just shared exactly what their customers said.”

Matt took the best of Wall of Love and created the Wall of Love 2.0. It was a simpler and more efficient mechanism to collect the tweets, review them in Slack and then trigger an action that would add them to the Wall of Love automatically.

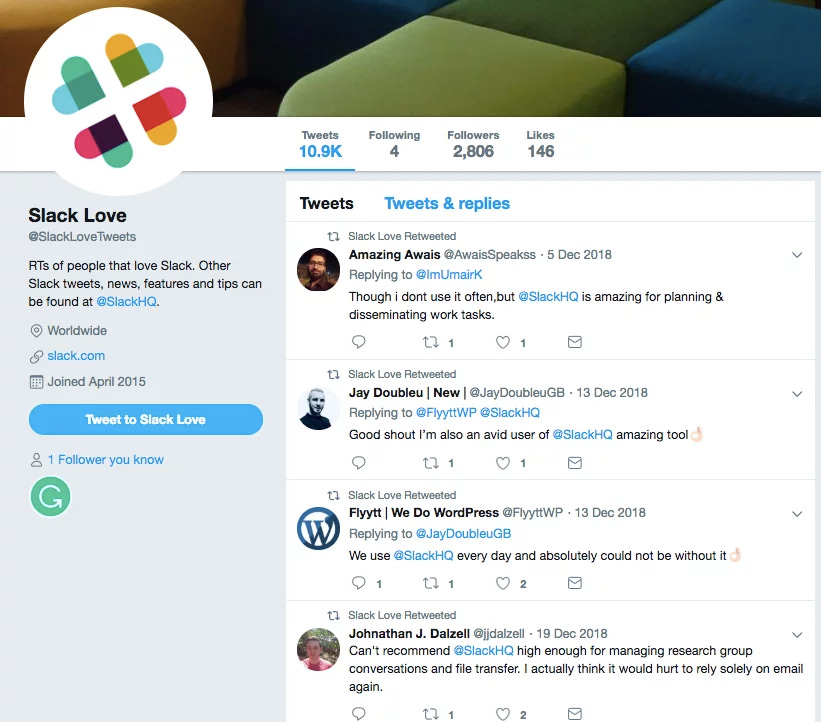

Then he created an even better version called @SlackLoveTweets.

I can’t remember if Matt created @SlackLoveTweets because Twitter killed the Collections product or the Slack Wall of Love simply outgrew it. No matter. Matt took over and created a dedicated new Twitter account — All Slack love all the time.

It even got its own 4-hearts emoji reflective of the original Slack hash tag logo.

Maximizing the Surface Area of the Company to Customer Feedback

Matt improved everything about the Wall of Love. He used some nifty programming skills to streamline the review / decide / post process. He kept track of the things people posted to us and shared them internally when appropriate.

He turned the account into a bi-directional point of access between Slack and our customers. From the specific lessons of the Wall of Love, we started to ask a question internally to generalize a new approach: How can we maximize the surface area of the company to customer feedback?

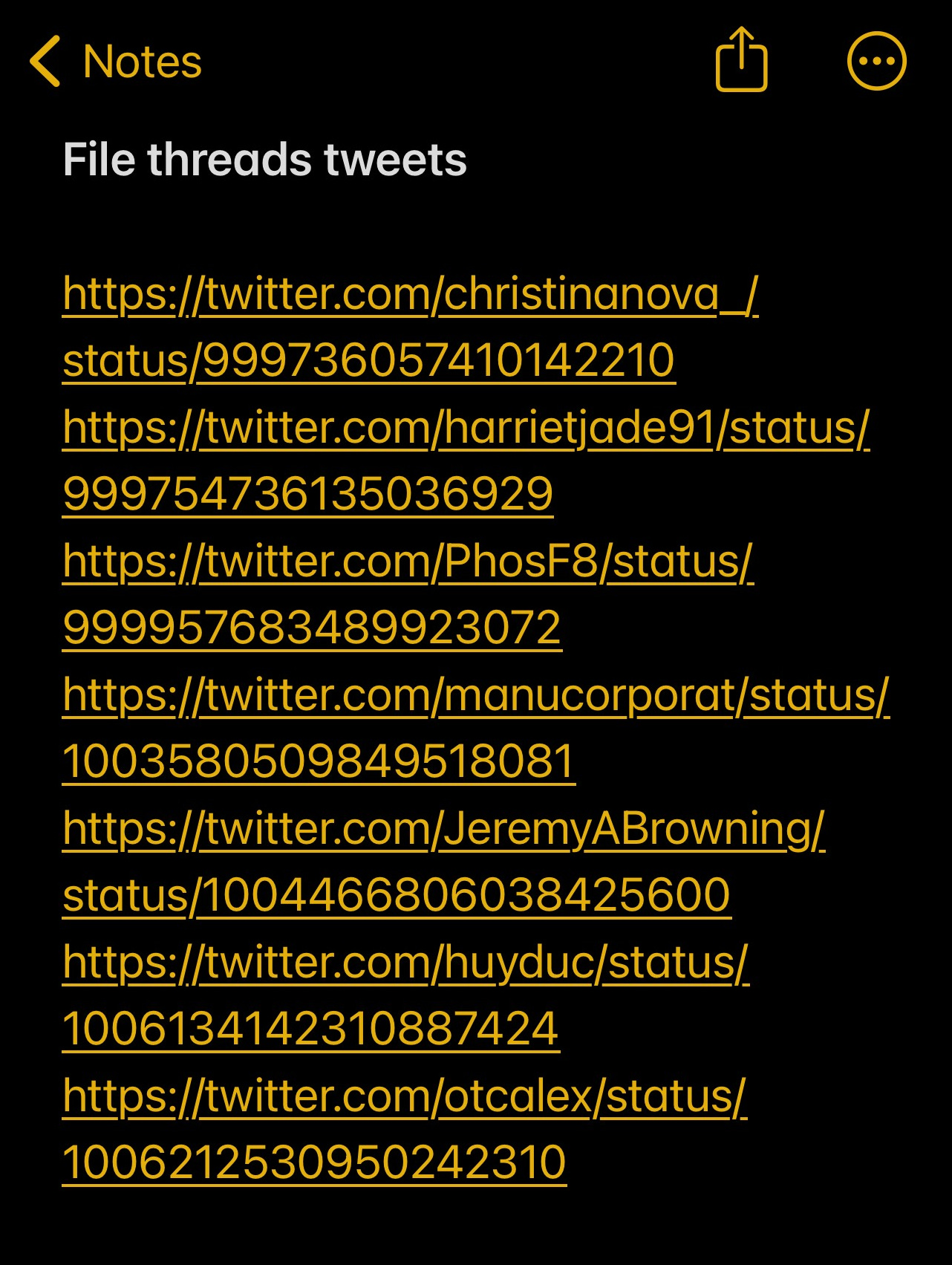

Here’s an example of that in action. Customers wrote to Slack on Twitter to request new product features, like having comments on files threaded with the file — a frequent request at the time. Or Dark Mode for Slack during the evenings. Or channel collections to manage their list of channels. Or, or, or — the list extended a long way.

As with most everything, at first we said no nicely. We appreciated the input and thanked them for it. But people still requested things. So Matt collected those requests in a simple Notes file and shared the collected feedback with our product team as evidence of a feature’s desirability. Here’s a screenshot of his Notes file for threaded file comments.

Then, when threaded file comments finally launched, (or Dark Mode or channel collections) Matt had a list of all the people who had requested it and @slackhq replied to each one of those people individually to say, “Hey, that thing you requested. It’s live now! Check it out here.”

As Matt said himself: “I think this was probably the 5th or 6th feature I did this for. We'd gotten so good at delighting people with tweet replies from Customer Experience that I started to track upcoming features in a similar way.”

And some feature requests took years to get to. But when we got to them, we still replied back to each original requester to let them know.

But it wasn’t easy. The barriers between our organization and our customers started very thin, and our ability to act and respond was very fast. Sometimes this surprised customers and mostly that was a delight for them. In short, we cared a lot about playing the Twitter game well, and we cared a lot about playing our overall game well.

In my own world, sitting next to the money, a tweet posted by someone always got a reply on Twitter from @slackhq. If it was about a deal or customer I knew I searched in our active teams to see about finding the same person. If I could, I’d also reach out to them by email.

In this fashion I ended up having a bunch of calls with customers about a feature called Guest Access. The feature would allow them to invite in a freelancer or consultant — someone they knew and trusted to work with the organization, but that wasn’t wholly part of the organization. Turned out, they wanted to only offer a subset of the channels in Slack to that person and to control their access to those channels. So the freelance designer got access to #project-redesign but not #internal-compensation or #hr-discussions.

This is all pretty deep into the weeds. But I’m diving in to highlight how hard we worked to maximize the surface area of the company to customer feedback. After all, we saw it as our mission to “understand what people think they want and then translate the value of Slack into their terms.” It was something we all worked on right from the beginning when Stewart wrote We don’t sell saddles here.

As our sales person, I found the most valuable role I could play talking with customers was as a conduit. I hosted the conversation and guided it in the directions I thought most fruitful. I took the notes and then shared those notes internally with the team and externally with the customer. Later we’d call parts of this work user research and product acceptance testing and customer success and all kinds of other formal things.

But to start it was as simple I’m describing — listen, guide, explore, note, share. And thank them for their time and help. Same as the Wall of Love.

Up next: