Values of the Slack Product: Part 1

Thinking out loud about the values we sent into the world. Reviewing The Real World of Technology and "the system of Slack." Seeing changes over time.

Do a quick search and you’ll find Slack’s corporate values easily enough. Salesforce acquiring Slack has not changed them from Empathy, Courtesy, Thriving, Craftsmanship, Playfulness and Solidarity.

More than a few pixels have been spilled discussing the corporate values of Slack as a company, including by me. (See, How Slack Built its Culture: Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 if you need to reacquaint yourself with what it means to Eat the Goat.)

But those values have (to my knowledge) all been about Slack, the organization, not Slack, the product. And I think it’s worth spending some time on the values of the Slack product, and how they changed over time. So that’s this chapter and the next one.

And to start, a hedge. I know. I’m sorry. This is not a Waffle House. And yet. Here’s the thing: I don’t really feel qualified to write about the values of the Slack product. But I haven’t seen anyone else doing it. And I think it’s an important topic to explore because every product has values, and those values show up in how the product is designed and gets used. In what’s easy and possible in a product, and what’s not. In a product’s defaults. In its character and tone and orientation. In what it enables and doesn’t enable.

I’ve added this chapter to the Dublin section because the values of the Slack product started to become more apparent to me as I was working in Dublin. I think this likely happened for 2 reasons.

First, because I was an outsider in Europe. I was more sensitive to how our product was matching up with different expectations from local customers, employees and contacts. How did Slack get received by UK financial services firms? By German manufacturers? By French software engineers? By Swedish media? It was not the same as the product had been received in the US.

Second, because the product began to change. As we worked with larger customers, key changes happened to make the product more suitable to larger customers, and those changes changed the product values.

For the first 3 or so years of Slack, product changes happened quickly and organically. We grew and rounded out the product in ways we could have good line of sight on. We knew our market well. We were our market. The features we added were features we wanted and could use in our own daily work.

But launching a totally new product called Enterprise Grid in early 2017 meant we had to build a product for organizations much larger than our own, who held different values than our own.

Those two reasons started to cause me to reflect on what we assumed about our product, and how those assumptions at the time needed to change.

(So when I say Slack in this chapter, I’m meaning the product, not Slack Technologies Inc., the organization. Clear as mud? Yes, right, onwards.)

Reviewing The Real World of Technology

Okay, take a second and zoom out with me. To add some additional background context on how I thought about the values of Slack, consider that I’m a person with an English major that somehow got a job in tech. And I felt very at home at Slack, among other liberal arts grads, in what we comfortably called a liberal arts software company. We had a broad grounding in social sciences. Our CEO did a degree in Philosophy. Going down the rabbit holes of humanities is on brand for Slack, so let’s go.

As a university student, I remember darkness came early in the winters. Driving home across the flat white of the snowy Canadian prairies, I listened to a radio series called The Real World of Technology on CBC Ideas.

Ursula Franklin wrote the book and gave the Massey Lectures. I won’t even try to summarize Dr. Franklin’s extraordinary life and career here. Look her up. She’s amazing. And listen to each of the five 1-hour chapters of The Real World of Technology on the CBC website. I strongly recommend them.

Anyhow, key parts of those lectures hit me and have stuck with me. They informed how I saw our work at Slack, starting with seeing software as just a current manifestation of humans integral ability to create tools to achieve goals.

Technology is broader than iPhones and java script and Artificial Intelligence. It’s not just new things that have debuted in our own lives. Technology is also digging with backhoes and sewing with robots and chopping wood with axes and lifting grain with augers and roofing our homes with asphalt shingles. It surrounds and shapes us every moment of every day.

From Dr. Franklin in the lectures:

As I see it, technology has built the house in which we all live. The house is continually being extended and remodelled. More and more of human life takes place within its walls, so that today there is hardly any human activity that does not occur within this house. All are affected by the design of the house, by the division of its space, by the location of its doors and walls. Compared to people in earlier times, we rarely have a chance to live outside this house. And the house is still changing; it is still being built as well as being demolished.

…

In this lecture, I would like to talk about technology as practice, about the organization of work and of people, and I would like to look at some models that underlie our thinking and discussions about technology. Before going any further, I should like to say what, in my approach, technology is not. Technology is not the sum of the artifacts, of the wheels and gears, of the rails and electronic transmitters. Technology is a system. It entails far more than its individual material components. Technology involves organization, procedures, symbols, new words, equations, and, most of all, a mindset.

So technology, in the Franklin worldview, is broad and inclusive, not new and isolated. And our current moment and its technologies are part of a continuum that reaches back as far as humans go.

So when I thought about how Slack was being received in Europe and how Slack was changing, I was thinking about the product in this long-run context. I was thinking beyond just the Slack application. I was thinking about what we might consider “the system of Slack.”

Slack always acted as the front end (software people often call this the top of the stack) of an intertwined system that extended to touch people and how they did things. It included their personal habits and preferences, their self identity and status in a group. It included their relationships with teammates and with their collected work, their reputation, their privilege and access to information. In short, it was a system enmeshed within their overall work systems.

I had always known that at its origin Slack reflected how the Slack team wanted to work. That position held up as part of our founding story. “We all agreed that, whatever we did next, we’d never want to collaborate again without using a system like this. So we thought it might be valuable to other people as well,” Stewart told the Wall Street Journal in a 2015 profile.

But what I think Stewart didn’t say is that Slack the product didn’t just reflect how the Slack team wanted to work. It reflected how they believed everyone should work. The Slack application made an argument for a way of working, for a system of work, reflective of specific values.

Starting Values of Slack Product

Below I’ve tried to specify what I think the original values of Slack were, and then to provide ways those values showed up in the product to illustrate. I’ve limited myself to just the top 3 values I noticed, for the sake of brevity. But there’s certainly a deeper conversation to explore in the system of Slack, with more examples that could include Slack’s Easter Eggs.

1. Default to Trust and Openness

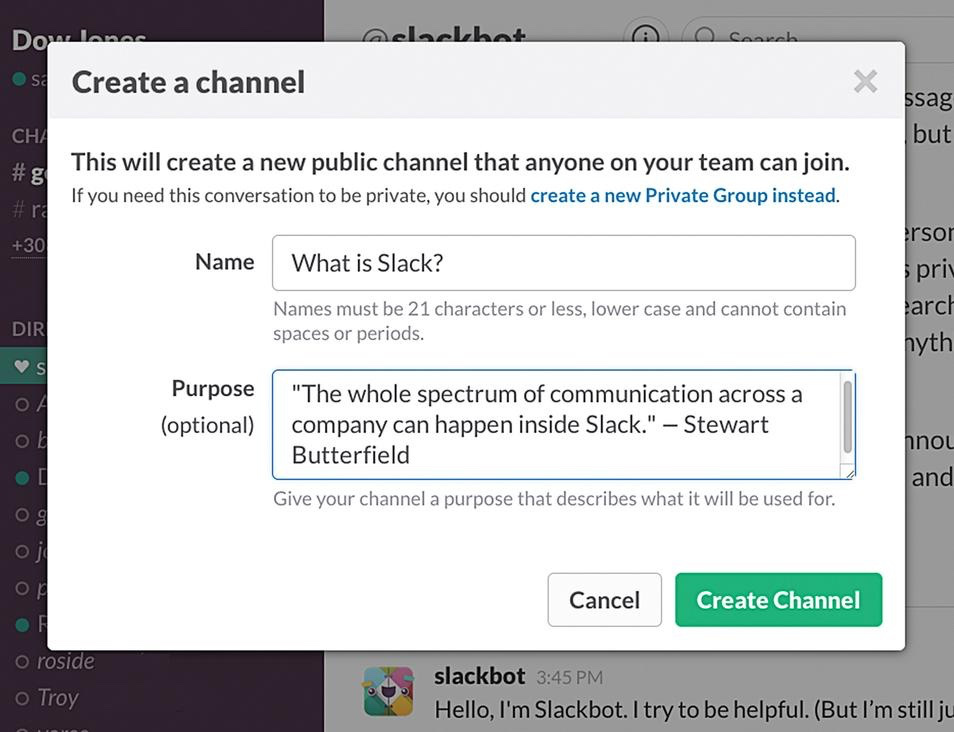

When people first encountered Slack the big thing that gave them pause was its default to trust and openness. The reaction I heard often was, “So, I post something and anyone can see this?” — the tone, clearly concerned; the asker, clearly holding reservations. Yes, that’s how it works by default.

By design, channels acted as the main mode of communication in Slack. Channels were joinable by anyone and searchable by anyone, where ‘anyone’ means anyone logged in to your Slack workspace. Anyone, we assumed, that you worked with. That meant that all work by default was available to everyone else on your team, unless you deleted it, or made the effort to post it to a private channel or direct message.

At the same time anyone could create a new channel, anyone could rename a channel or change a channel topic or description. The default controls for the main mode of communication in Slack were no hierarchical controls. Instead, the default was to trust all the users of the system to be good actors, to let them edit things, and to show who had done anything.

The only real check to this openness and trust was that all messages and actions you did in Slack were attributable to you. There was no anonymous contribution or consumption. If you changed a channel topic to “Stewart sucks donkey d!cks” that would show up as your change. Your teammates could see that you changed it. Transparency and reciprocity in that transparency meant the product held people accountable, and nudged folks so that everyone trusted each other.

Building Slack for trust and openness said to our customers that we believed in them and that they should default to trusting their teammates. They were all trustworthy. Teammates were good actors. And, if not, then you’d find out pretty quickly.

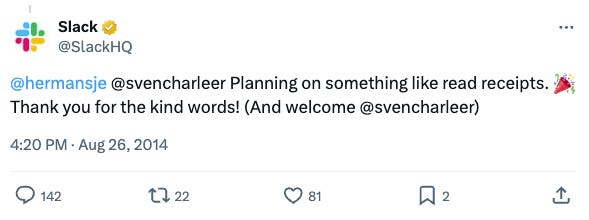

To emphasize how Slack oriented towards defaulting to trust, consider a feature that was not built: Read receipts. Read receipts are those small bits of text telling you someone has seen your message. Slack didn’t have them because we said no nicely as a practice, and what good could they do?

If you wanted someone to acknowledge they had received your message, you could simply ask someone to do so. (“Please give me a 👍 when you see this.”) Having the product tell you someone had read your message, without adding any more value or context, just invited people to create stories in their heads about what was happening.

2. A Shared Reality

With channels as the default mode of communication, everyone in Slack by default also had the same view of the work going on. Everyone saw the channel the same way.

This consistent access and visibility of information contrasted with how people were used to working in email. With email, everyone’s inbox was separate and unique from everyone else’s. In Slack, everyone’s view of the information was common, shared and consistent. Everyone had a shared reality.

To illustrate the contrast of Slack vs email I would often ask folks — have you ever seen a co-worker’s inbox? Has that co-worker seen your inbox? The answer was almost always, “of course not.” Their inbox was like their underwear — private.

But if email was how they worked together, then each person in the organization had a separate, siloed view of the work. There was very little shared reality or context for what was shared, so no one ever knew how much anyone else knew.

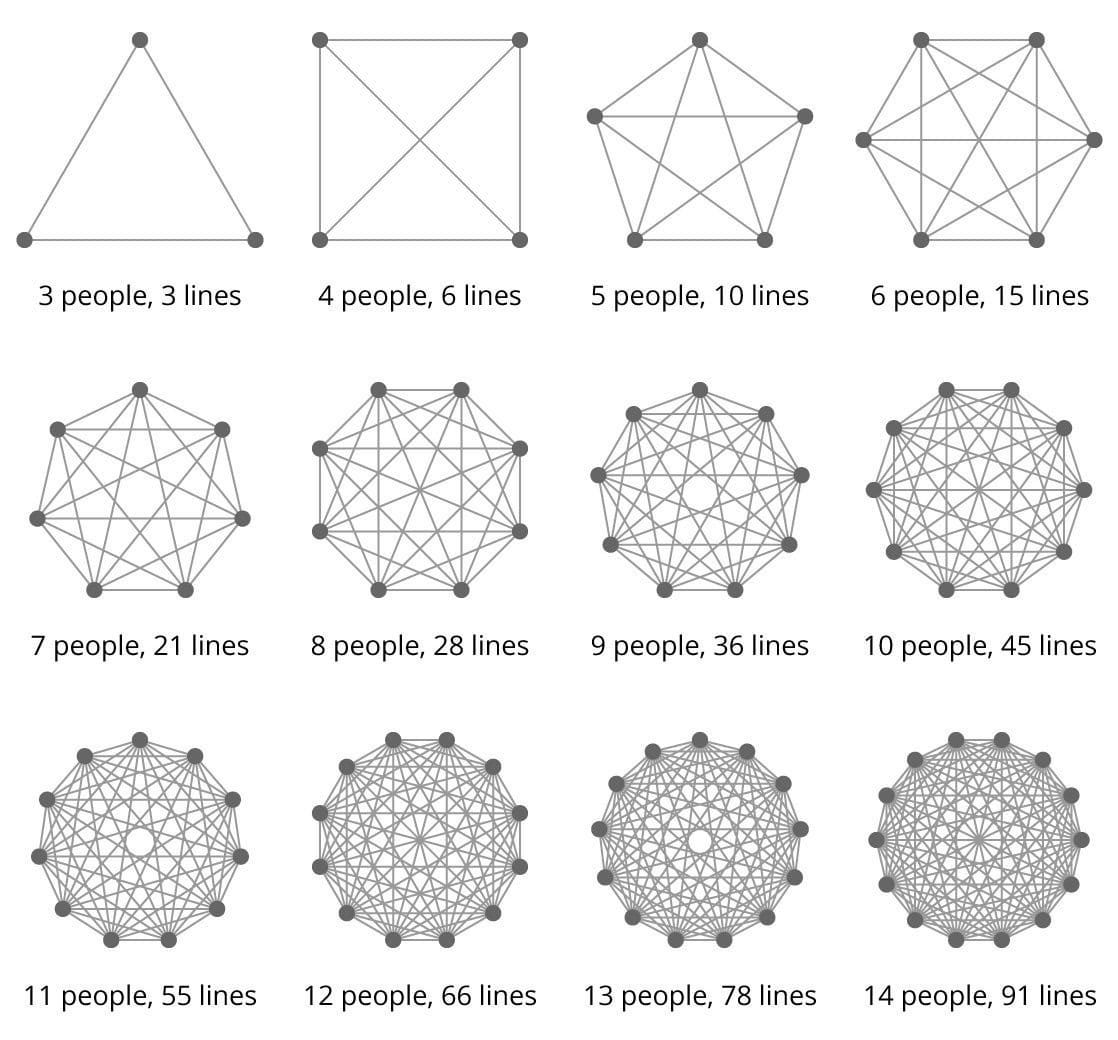

Sure, in an email world, sometimes work got shared through CCs and BCCs and mailing lists, but the fundamental model of communication had each participant seeing a different view, and with very little clue to what their teammates saw. Each person was an endpoint in a network.

And people pretty universally hated email. The default settings of “the system of email” was closed communication and near zero visibility between teammates.

And people acted in line with how the defaults of that model worked. Information hoarding, using information for power, lack of clarity on updates, inability to find information, uncertainly on who knew what, did you get the latest attachment? — were these antisocial behaviours because of email or was the design of email because of these behaviours? Yes. There was no shared reality.

Over time we got pretty good at seeing if a team was succeeding or not with Slack based on how much they communicated in channels, or how much they just used Slack like instant email. The more a team posted in channels, the better they performed. The more they reverted to direct messages and private channels, the less value they got from the product.

It was really a great example of how a technology exists beyond the bounds of the product. If a team used Slack like a system of email, they didn’t really work too well. If they used it like a system of Slack, they took off like gangbusters.

3. Compassion Through Service

That’s why what we’re selling is organizational transformation. The software just happens to be the part we’re able to build & ship (and the means for us to get our cut).

We’re selling a reduction in information overload, relief from stress, and a new ability to extract the enormous value of hitherto useless corporate archives. We’re selling better organizations, better teams. That’s a good thing for people to buy and it is a much better thing for us to sell in the long run. We will be successful to the extent that we create better teams.

— We Don’t Sell Saddles Here, Stewart Butterfield

Right from the start, we knew we were asking a lot of our customers. Even if Slackbot provided a great welcome. Even if the sign up process flowed effortlessly. Even if it proved simple as chocolate cake to get your teammates using Slack every day. Even if all these were true — the thing we were asking of customers remained very hard.

So we had to help. Each small step that it took to use the system of Slack, and each small step to improve your use of the system, and to be maximally excellent, we wanted to help. We had to apply to MAYA principle of Most Advanced Yet Acceptable change to every part of our business. And all delivered through a service mindset.

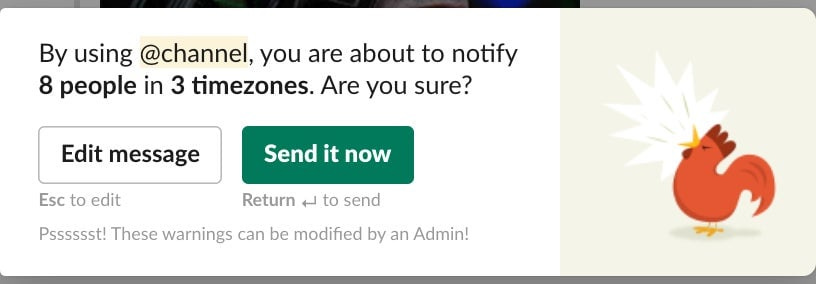

In the product, that meant some guardrails to help people make good choices. Shouty the rooster would warn you if you were about to wake someone up with the notification from your message.

If you ran into problems, that meant we had operators standing by to help out. Type /help in Slack and you could start a new ticket to get help. Email help@slack.com and you could start a new ticket to get help. Tweet to @slackhq and you got an answer. We were asking a lot of our customers, we had to stand up and help them.

And it helped us too. We talked about how we could “maximize the surface area of the company to customer feedback” because the more feedback we could touch, the better we could learn what our customers needed. Customer Support acted not as a cost centre but as a critical contact point between the system of Slack and our customers. We staffed it with very capable experts.

And I’ll tell you a small secret. We sold a specific response time to paid customers. Open a ticket with Slack and you’ll get an answer from an expert human within 4 hours. We had separate queues for paid vs free customers, to triage and prioritize. But we actually gave answers from experts humans to everyone within 4 hours, including customers on the Free plan, not just paid customers.

There were decisions within Slack that felt like they were made because of a principle, even if it was going to hurt aspects of the business, with the idea that being compassionate about our customers, in the long run, was going to make us more successful.

Jessica Kirkpatrick, a senior data scientist, Will Slack Change Work Before Work Changes Slack?

Seeing Changes Over Time

When we started, I think the values built into the system of Slack created its appeal. Be Less Busy wasn’t a statement about task lists. It was a statement about the feeling individuals could aspire to in their work. It was a feeling we hoped to deliver through our product.

Much of the time those values were highly welcomed: more trust and openness in work, a shared reality to rely on, a dedication to compassion through the delivery of a service. But not always. Or, at least, not always as the top values.

“In fact your experience of someone else that you work with if you’re a Slack-using company is often principally via Slack, that’s how you experience your colleagues, most of your interactions.”

— Stewart Butterfield, Stratechery, “Slack Launches Slack Grid, An Interview with Stewart Butterfield”

For pretty much all work places that used Slack, a transference of emotion happened between how they felt about their work and teammates and how they felt about Slack, and vice versa. But as we worked with larger customers, they needed different things and held different values.

What are large enterprise B2B software values? Control, reliability, predictability, growth, security, professionalism. Not exactly matching up to the system of Slack, right? They saw Slack and perhaps wondered if Slack undermined and threatened their control. They liked the promises of the system of Slack — fewer meetings, less email, more productivity. But they had different masters, different values at the top of their list. Some maybe even hated Slack because of what it could represent.

I don’t mean to make large enterprises out to be villains here. They needed to make decisions aligned with their incentives. In defence, openness could be a threat. If you are a telco or utility with a large captured market of customers, you might oppose all change that could threaten your business. Big equals conservative because of the size of risk of what can be lost.

So what could we do? Either we decided to remain focused on organizations who received our product and loved it, and limit the number of customers we could appeal to. Or we adapted the product to find and accommodate new customers, and larger customers, and customers in regulated industries and conservative cultures.

I bet you can guess what option we chose. And that, dear reader, is part 2 of the story.

Up next: Values of Slack Product: Part 2 — Finding what large customers needed. Becoming carrier grade. Launching a new product called Enterprise Grid.

Curious about Franklin’s “technology is a mindset” - how would you describe this mindset that birthed the Slack values? What is its foundation?

Love the dissection of Slack's product values versus corporate vaules. The point about defaulting to openness being a shock for new users is so true, I remember early adopters freaking out about public channels untl they realized transparency actually built trust faster. The tension you describe between startup ideals and enterprsie needs captures a genuine dilemma, selling to big orgs means accepting their preference for control over speed.