Billion with a B

Living a fundraising announcement from the inside. Framing it for everyone. Creating the chance to tell our story. Finding the flywheel.

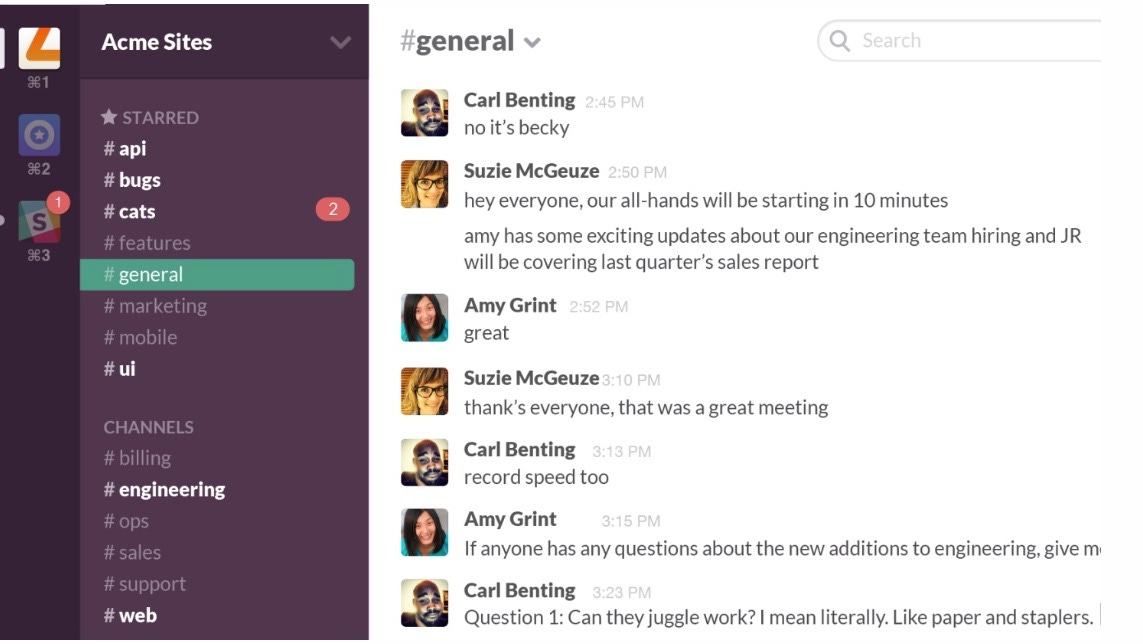

One morning a little more than 8 months after launching paid Slack on February 12, 2014, I started my work day doing what had become my usual routine at Slack.

I checked my messages and tasks from home. Anything needing action or a quick update? Done. Got on my bike, commuted to the office. On arriving, I checked back in. What was important? What needed tending? Anything noteworthy? When’s my first call again?

I started my work and got immersed in what a customer needed. By the middle of the morning I poked my head up to see what was going on. I heard a rumour — we were going to announce a new round of fundraising. Hunh. The rumour was news to me. I would have to be just like everyone else and wait to see what it all meant.

And when the news came out, it felt big and important. It must be, right? There were big numbers and plenty of news coverage. About a week before, Stewart had asked me for a list of our biggest customers, as he always did for big announcements. So I knew something could be up on the PR front. But truthfully, it all felt somewhat mystifying.

The news was: we had raised lots of money — $120-million. It was from the best venture capitalists in the world by reputation and status. Our existing investors (a16z, Accel and Social + Capital) had been joined by some new investors (Kleiner Perkins and Google Ventures) and all had bought Slack stock.

This was all pretty straightforward and standard for a top-tier growing tech startup. And somehow that had become us, Slack. We pinched ourselves a bit and reflected for a few seconds on our journey. It seemed pretty impossible for it to be any better.

Then the kicker. A second and bigger story for us beyond the headline: Slack was worth a billion dollars, even before the new money. Slack was worth a billion dollars. “Billion” with a “B.” Holy shit. What did that mean? What could that possibly mean?

We didn’t really know. At least, that felt like the general sense from anyone I spoke with in the Vancouver office. How could we know? It seemed like play money, like we had all of a sudden learned how to defy gravity or read minds or conjure fire from farts without a match.

The only real frame of reference I had for a billion of anything is something my brother taught me. If money were time, one million seconds equals 11.5 days; one billion seconds is 31.5 years. The difference of one letter from million to billion masks the scale of the difference. We sort of group them together as big numbers. But they’re very different. A million dollars is ten years of a 6-figure salary. A billion dollars is 10,000 years of a 6-figure salary.

Once you thought about it, if you thought about it at all, a billion seemed perfectly unfathomable. Absurd. A number too large to comprehend. So I mostly didn’t think about it.

Being Unicorns

The category of private tech startups worth more than a billion dollars got called ‘Unicorns’ in the press for a good reason. There was a mythology to the milestone, a great story encapsulated in a label for an abstract valuation. Cresting the billion-dollar threshold became a sought-after rite of passage for a startup. It meant you’d arrived, somewhere, somehow. There would certainly be lists.

But here’s the thing. News came out that Slack was worth a billion dollars and nothing changed for us, day to day. We were worth a billion dollars. We went back to our work. We tried to do our best. Nothing changed, too much. Or, so it seemed at the time. Yet change stalked us and we could feel it closing in.

The only sensible response in our small Vancouver office to the funding announcement was to acknowledge the event, appreciate it felt significant, appreciate we didn’t really understand it, and then get back to work doing the things that had led us to success so far — that had led us to be a billion-dollar company.

So, that’s, as far as I can remember, what we did. I had another customer call coming up in 12 minutes. I needed to prep. Was anyone going for burritos for lunch?

I cast my mind back and wonder: did Stewart also post something internally about the fundraising? Almost certainly he would have. It would have gone live around the same time as the news broke.

Yet I can’t remember any of the specifics of it. It blurs together with all of the fundraising announcements that would follow over the next few years and drive the value Slack to larger and larger billions.

Each funding announcement was its own event. Yet they all had a consistent and coherent message that came directly from Stewart and Slack’s leadership team:

We’re raising money. It’s a very good time to raise money. There is a lot of demand for Slack among our existing investors and new investors are interested too. Did we mention it’s a very good time to raise money?

Slack is a special company. Our growth is different from others you may hear about. Our product is different. Our opportunity is larger than any other business-to-business software company because everyone in every role at every company can use Slack.

This money isn’t for any specific purpose other than operations and expansion and flexibility.

The most important 6 months for Slack ever will be the next 6 months.

In a larger sense my marketing brain started to see how fundraising became a key part of our story at Slack, like market positioning and customer stories. We were a unicorn worth a billion dollars. We didn’t know that meant. But others paid attention to it. That news broke through for people and got them to take notice. People outside of Slack almost always wanted to talk about it, especially at large customers.

The fundraising announcements acted as proxy benchmarks for our importance in the world. Our increasing valuation acted as a signal to them. The herd mentality and fear of missing out (FOMO) kicked into gear. No one wanted to be left behind on the newest new thing.

But to us Slack employees, our fundraising activities didn’t get any special treatment. No one signalled to us that it was more important than any of the other things we had to do. We didn’t drive our business in cycles to increase its appeal for another round of financing. We didn’t goose our numbers for investor presentations. The money truly did bring us the flexibility to run the business and work in the business and not need the money.

In the business, we tracked the numbers to know our business because those numbers were how we knew our business. Those numbers also happened to be the numbers that prospective investors might be curious about to also know our business. And those numbers just happened to be very consistent and very good. But we didn’t track numbers just for investors.

We had our story. We built our business. We had our proof. The combination proved very compelling to everyone and kept everyone oriented to the same measures. And it gave us a bigger chance to tell our story.

Storytelling and the PR Flywheel

When we first became a billion-dollar company at the end of October, 2014, we landed in the midst of some very favourable media coverage from top flight media outlets. Such as, Why Slack is worth $1bn: it’s trying to change how we work, that opens thusly:

There are two types of people in the world: those who have never heard of Slack, and those who can’t imagine life without it. The latter group explains why the workplace chat app has just received $120m investment valuing it at $1.12bn. Not bad for a product launched just over a year ago.

Stewart still posted the story of our news internally. He wanted us to hear it from him. But the internal message of the news felt much more modest than the external message. The external message proved to be gold. And it didn’t happen by accident.

We had a terrific PR team and we used PR as a key marketing tactic. The PR team worked every day behind the scenes to orchestrate our coverage (so much more could be said here! Message management. Relationships. Sequencing of the story. Who got access. It was masterful.). Sure, it certainly helped to have excellent numbers that we led with and that acted as proof of the story we wanted to tell — this is real and big and inexorable.

And it certainly helped to have a very credible CEO who could dig deep into the numbers in one sentence and then zoom out to say, “The world is in the very early stages of a 100 year shift in how people communicate, and we’re determined to push the boundaries. As the leader of a brand new product category, we have a huge advantage right now.”

But still, the coverage was fawning and consistently and almost embarrassingly excellent. It proved an important factor in our continued growth — a key driver in our overall business flywheel.

Great stories drove more interest and sign ups and receptiveness and the perception that we were real, not going anywhere, and actually making a huge difference for our customers. No one wanted to miss out or be late to a 100-year shift in how people communicate!

Customers often asked on calls how the fundraising affected our business. Now that we were a billion-dollar company, what was different? They wanted to know what it was like inside. An element of celebrity rubbed off on our business and product and lubricated conversations and processes.

PR worked like gangbusters because we had a compelling story to tell. We had a compelling story because we had a great product. We had a great product that served terrific customers. Those customers raved about the product and generated the proof of its effects. Those points of proof got captured and relayed to a savvy, charismatic and talented CEO to tell our compelling story, driven by a world-class PR team.

Rinse and repeat, on and on and on. Each piece of our work contributed to the whole. The flywheel spun because we all pushed on it. And we haven’t even touched on the top notch brand, the technical operations, the security team, the legal team, the finance folks, etc., etc. As Stewart wrote right at the beginning in We Don’t Sell Saddles Here, marketing was something we all work on.

And it was all about to get even bigger and even a little bit famous.

Up Next — Slack Gets Kinda Famous: Slack in the wild. Hosting Jared Leto and his Oscar. Tweeting with Snoop Dogg. Finding new office spaces.

I am going to use “conjure fire from farts without a match” in the future. I’m not sure how, but it will happen.