Launching Paid Slack

Asking to get paid for Slack. How we decided to launch. Tactics we used. Credits and the mechanics of our business.

From the very beginning, Slack was going to be a paid product. We knew our business model, our customers and how we wanted to get paid.

This simplicity on the business we were building may seem like a small detail in hindsight, but it provided us with a huge amount of clarity as we built up to the launch of the paid product. Our business was to convince people to pay us to use Slack.

On calls customers would sometime ask me if we were going to offer advertising to try to monetize our users, like a consumer product. Some kind of Facebook for small groups? We were not.

It was always very clear that we were going to be a B2B — a business-to-business software as a service company. A free version would exist but people would pay to use the full version of our software. More precisely, companies would pay for their people to use the software. We hoped.

People I spoke with loved to hear this plain and direct answer, despite its implication that using Slack would at some point in the future cost them real cash money. It said to them that we knew who we were and it made clear our terms of engagement with them. It also made clear that they were not the product to be served up for advertisers. They were the customer.

Their companies already paid for their people to use other software. We would slot into that same kind of business model. Easy peasy.

At the same time, we understood that paying for something new wasn’t a given for our customers. So when we delivered it, we made sure to pair our commercial message with a companion message that Slack would continue to offer a Free version they could keep using for an unlimited time with an unlimited number of users. So: upgrades coming but we wouldn’t kick them off.

With this clarity about what we were building, we had to do the thing we intended and launch that paid product. Right, let’s go!

Ultimate SUCCESS!

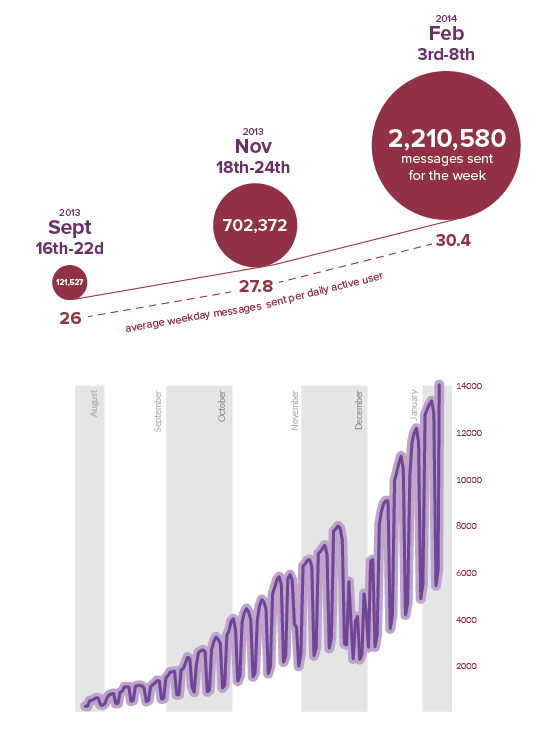

As we started 2014 we knew we had some strong tailwinds in our favour. We now had ~4 months of data on people using the product and we started to see some distinctive patterns that let us tease out some generalized analytics.

In a spreadsheet called Ultimate SUCCESS! we had an export of data that itemized our users, organized by weekly cohort. And we could see two distinct trends that would come to define our product launch, our business success and the future trajectory of the company.

Once teams started using Slack they pretty much never stopped.

And better yet, teams that started using Slack grew in size over time.

Both these vectors of growth showed up right away and showed up in so steady a pattern that it was almost eerie. It seems simple to describe these two patterns now, looking back, but their effect proven profound and foundational to our success. If these two patterns held true (and we could see no reason they would not) we could run a very successful business.

(Quick warning: math ahead! If seeing how the sausage gets made isn’t your preference, feel free to skip ahead to the next heading, Countdown to Launch. There will be no test.)

Deeper into the weeds, in the Ultimate SUCCESS spreadsheet we unpacked what we could see in the weekly cohorts of Slack users (who signed up that week). In a note on the first weekly cohort on September 5, 2013, Stewart had written:

(This week) 906 invites have been sent. Out of those, 524 teams have been created (58% acceptance). Out of those, 66 teams had at least 3 active users in the last 24 hours (12.6%). If you exclude teams that are less than a week old, the number is 51 active out of 446 teams created (11.43%).

Of 906 invites sent, we've gotten 66 active teams so far (7.3%). That's a bit better than I was hoping we'd do overall (5%) but it is early days: more of those invites will get accepted over the next while and some of the active teams will stop using.

Get beyond the small (though bigish to us at the time!) numbers and the path ahead for Slack’s growth appeared.

When we invited people to try Slack, they tried Slack at a high rate. They also invited others to try Slack with them. Most did so right away and fewer did so as their invitation aged. But they still often did act on the invite after a period of time, a week or a few weeks. So they didn’t show up in our numbers yet but they might. Time was on our side.

Stewart was also proven right that it was early days. More of the invites did get accepted over the next while.

But he was wrong that some of the active teams would stop using Slack. Once started, so few people stopped using Slack that we could basically assume that no one stopped using Slack. Churn didn’t really exist for our product.

And if we’re doing math, it’s also worth dwelling here on how we were starting to define an ‘Active’ team, in a fairly rigorous way, as a specific number of users logged in over the past 24 hours. We refined that idea over time and it became a very good indicator of the propensity of a team to keep using Slack. Once they reached a specific threshold (something like 4+ active users on 4+ days of 7 rolling days and sending 50+ messages) we had them. They were Slack users and would keep using Slack for as far as we could foresee.

The following week’s cohort, September 11, 2013, 9.92% of invited teams became active. The week of September 18, 2013, 10.15% of invited teams became active. We started doing some bigger runs of invites and the conversion rate for the first week of activation dipped a bit to 7%, but that wasn’t including all the teams invited in weeks prior as well — those slow to act on their invitation — who became active.

At the same time as we invited teams to use Slack, more people were signing up all the time to get an invite to try Slack. The pattern continued: more sign ups to get an invite, a high conversion rate from invitation to trying Slack, a high conversion rate to adding people and becoming an active team.

By the time we neared the launch of our paid product on February 12, 2014, we were still seeing conversion rates of 5-7% / week for newly invited teams to become active.

Anyone with knowledge of compounding interest can see where this story is going, if the growth keeps up. Small numbers can get big quickly. But that’s all projection and, if you know the story, burnished with hindsight.

At the time, there was no guarantee the growth would continue at such a blistering pace week-over-week. Our modest success still felt pretty fleeting, like a small flame that we needed to protect and nurture just the right amount, adding kindling that we believed to be dry enough to burn.

Each week when we reviewed the Ultimate SUCCESS numbers as a team we each felt a certain vagueness of growth symptoms in each of our various functions. There were more emails to answer. More passwords needed resetting. More traffic to the web servers. But it still felt tenuous and like it could end any time — midnight striking at Cinderella's ball — and we’d be left again in obscurity, struggling to figure out anything that might work.

In that weekly meeting, as we looked at the numbers together, it always seemed like our dream could still be real, or not. We could be a huge success or a crashing failure. Everything was in play, even as the weeks went by and the numbers kept going up and to the right. Then slowly, skeptically, we started to recognize that the trend line was not just holding but accelerating.

The numbers kept getting better. The growth kept happening and happening faster. Really? Really. So far. We nodded and wanted to believe but kept repeating the Russian proverb, “Trust, but verify.”

Countdown to Launch

The numbers whispered to us: it was time. We knew it too. It was time. We had to really go for it and see if we had a fire that would burn.

We set our launch date for February 12, 2014. The list of tasks to accomplish prior to that date ended up on a new burndown list.

Leading up to our launch date we had a flurry of activities. Through our investors at a16z we started to work with a PR team called Outcast. They were pros and jumped in with both feet, crafting a story for us that matched our evidence and that appealed to the press we needed to cover us.

Our numbers were strong so we wanted to lead with those as proof. Our customers were succeeding so we needed to get them standing behind our story and corroborating it. All the elements were in place and the story shaped up well with its two key levers of proof to pitch:

We had real data that showed our customer growth.

We had real customers using our product who wanted to talk about using it.

Those two levers proved strong and compelling. And that was good because we’d been investing tons of our time and effort into building them.

All that talking with customers I’d been doing, noting what they said, playing it back to them to get confirmation, then asking if we could use their words in our marketing? Yes, friend, that was the good stuff and here was the first payoff.

As a bonus, we weren’t alone telling our stories. Is partners the right word here? Maybe advocates would be better. Interested parties. Friends, certainly, who wanted to see us succeed. Folks with clout and status and audience, not to mention financial interest. Insiders.

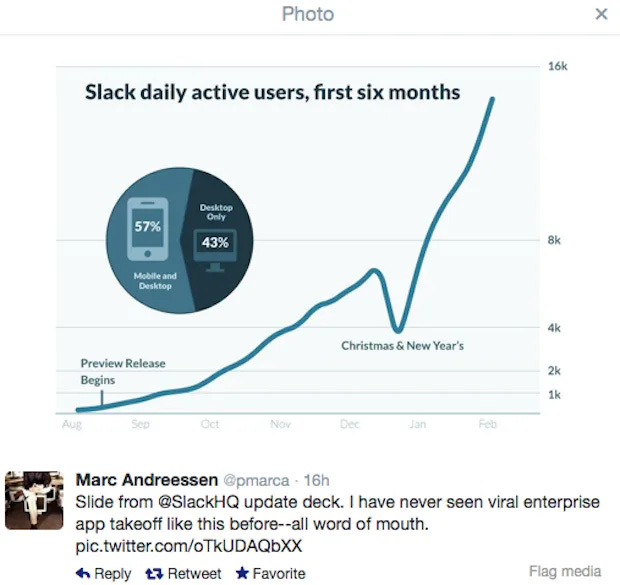

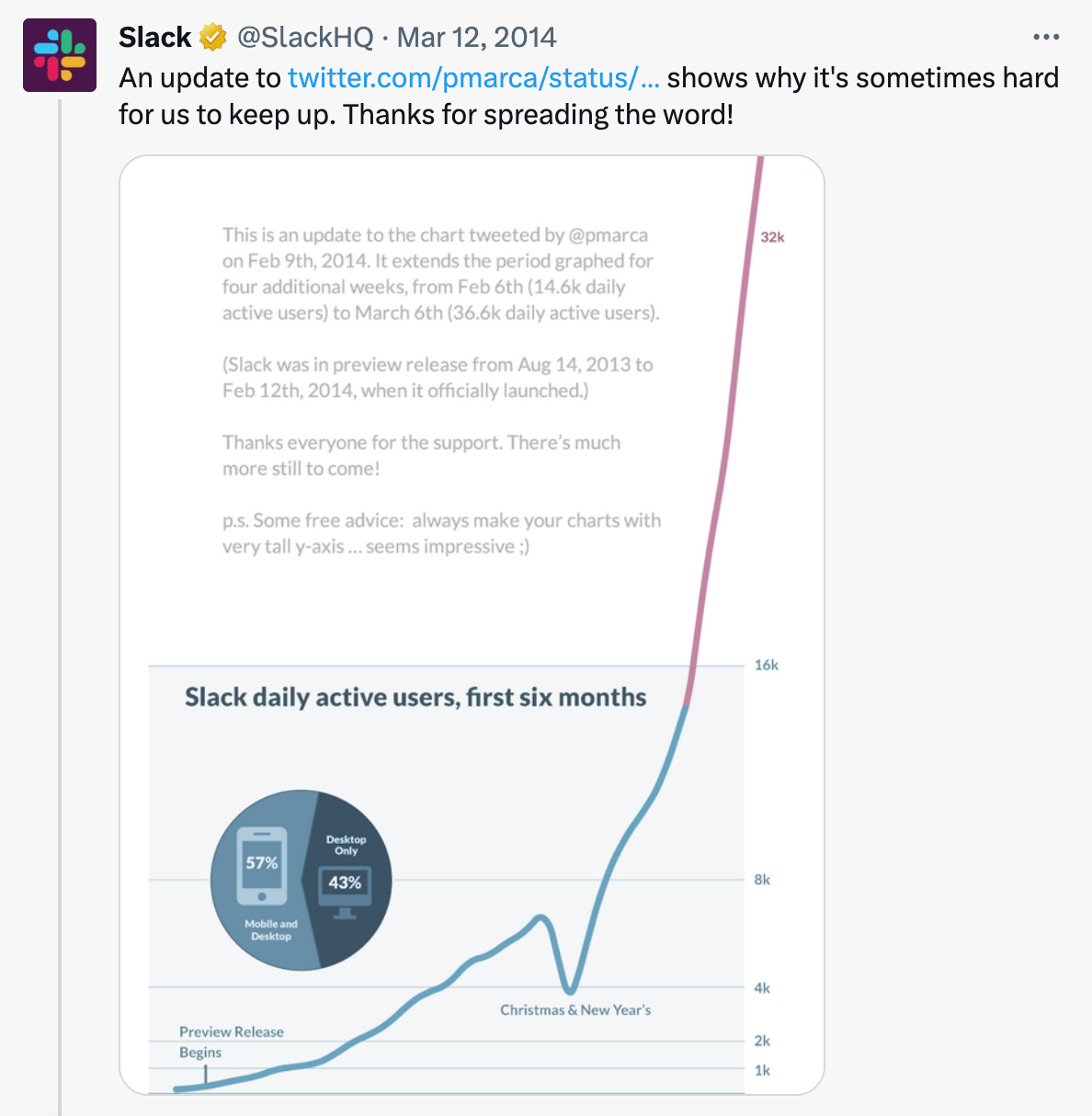

One was Marc Andreessen, Slack board member, shareholder through a16z and pretty famous tech nerd guy. He certainly knew the Twitter game. He just needed the right graphic to post on February 9, 2014 to create an epic tweet that drove a ton of ‘earned impressions,’ as the PR folks would say, and seeded the story we wanted to tell for our launch day of February 12.

Launch day approached and our burndown list mostly shrank. Items we deemed too hard or not high enough priority got pushed to Later in the status column. A calm clarity settled over the team as we pulled in unison toward what we hoped would prove to be our big moment.

And yes, would it work? All the psychological rationalizing we did couldn’t really prepare us for the binary truth of the moment we had scheduled. Either people would pay for Slack, or they would not. One way, and we had a business that could be valuable, with all the supporting elements: jobs, offices, a future. Another way, and we had to go back a step and figure out what we had, if we had anything.

In hindsight this uncertainty and risk seems misguided or diminished because we know how the story turns out. But at the time I cannot stress enough how fragile it all seemed. We knew nothing!

Slack was built from the ashes of a company that had blown its brains out hiring people to build a beautiful and complex game that no one ended up willing to pay for. It ended up more like an art project than a business. That failure motivated us. It terrified us. Everything seemed good but still, once more: Trust, but verify.

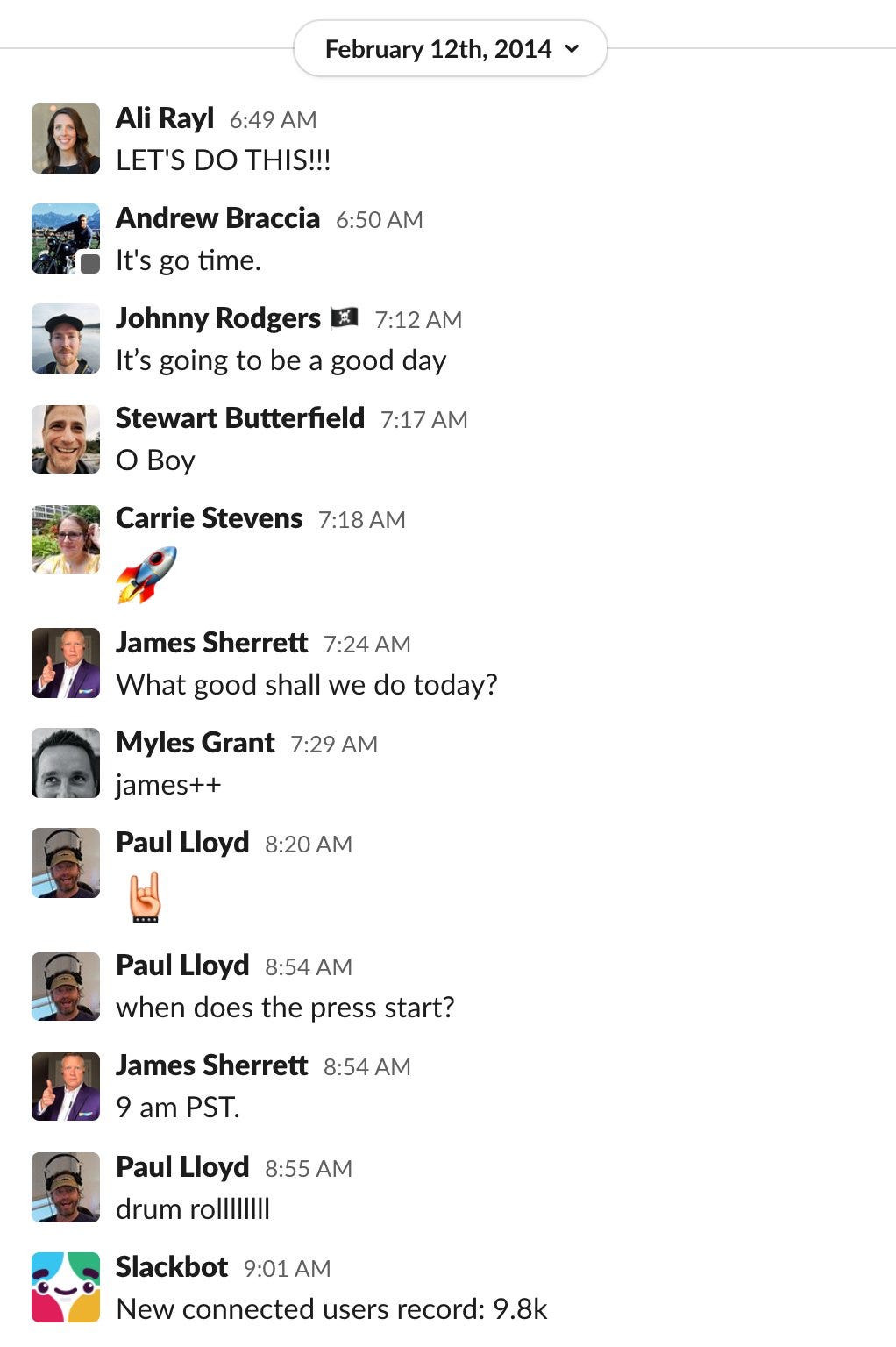

Go Time

Launch day arrived and we dressed up as well as tech nerds can for the occasion — a few jackets, a few ties, some of the best hoodies in the closet. Here’s our Vancouver crew, spiffy as we could be.

An email went out to all the administrators of Slack instances that they could now upgrade and pay, should they choose to.

And what did the administrators who received those emails do?

The best possible thing. They started to pay, right away, even though they didn’t have to. But it was easy to pay because they paid in a currency we’d created for them: credits.

$100. $250. $50. We added credits to our customers’ accounts, sometimes automatically for everyone, sometimes tactically for special consideration. We wanted it to be as easy as possible to upgrade and taste the full product, with the theory that a luxury once enjoyed, becomes a necessity. Plus the upgraded product had some pretty great benefits for anyone using Slack.

As we saw people upgrade and use their credits, and as we heard their feedback, we kept running experiments on the number of credits to add to customers’ accounts, and how to tell people about the credits. We even learned a few lessons on how credits influenced upgrades.

Overall, I believe the credits were a masterstroke and incredibly successful. They felt like a soft transition for folks who had been using a product for Free and now were being asked to pay. Credits soothed the pain. They also changed a single message (Pay now, please!) into a two-part message (Pay now, please! With this gift.) Then when the credits ran out we’d charge their credit card. They just had to put their credit card on file to use the credits. They could always downgrade before we charged their card.

And truthfully, we gave away credits like they were free. Like virtual money fairies we sprinkled credits on accounts and then told the customers about them to see if they were interested in trying the paid product.

Were the credits free? Not really. But kind of.

Symbolically, we felt like they said to our customers that we believed in our product and we understand transitioning to paying might be hard, so these credits will make it easier. But practically, if customers also believed in the product and got value from it, the credits acted as simply deferred revenue. Again, for practical purposes, no one stopped using Slack, so credits just pushed back when customers started paying money for their upgrade.

We even let customers earn their own credits through a referral program we called Give 100 / Get 100. They could give $100 of credits to a new team starting to use Slack. If that team upgraded, the referring team also got $100 of credits. The old win-win proposition in action, led by the giving.

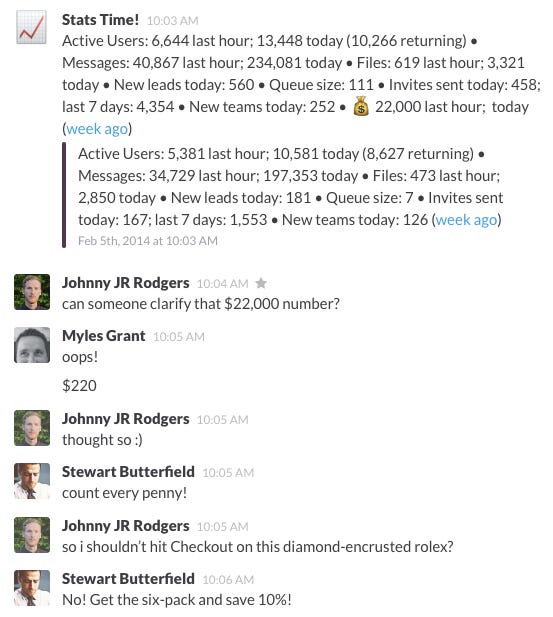

And people signed up. People used their credits. People moved to the paid plan right away. Here’s how that looked by 10:03 am Pacific time on the morning of February 12, 2014, though a bit overstated.

Was it important that we called the credits in each customers’ account a Thank You gift? Yes, I think it was because these were the people who had risked their own credibility at their respective organizations to start to use Slack in the first place. It felt very much like a social contract we were establishing with our customers. They had helped us. We wanted to help them too.

Our preview release period (what we called the time from August 14, 2013 to February 12, 2014) hadn’t been flawless. We had down times when Slack proved slow or unreachable for users. We had simple outages when Slack was b0rked. Through those pains, people had stuck with us.

Sure, they might have yelled at us on Twitter or written cross emails. They might have gotten frustrated with us and vented online. That in itself wasn’t terrifically good (though we did our best to respond to every single person and hear their issue and turn the shortcoming into a chance to be human with them, ask for forgiveness and keep them updated). But it meant people cared. Sometimes people complained about Slack being down even before we knew it was down.

The polished turd of those times when Slack was down showed us that our product had real value to people using it. Our product was essential and valuable to our customers’ work. Now they showed us the ultimate proof and paid that real cash for it.

A month after launching Slack’s paid product our growth continued and had even continued to accelerate. We had trusted and now we had verified.

As the person responsible for working with customers and helping them pay for Slack, the demands of my job followed the line in the graph above pretty closely, and that meant pretty much vertically. More upgrades, more teams, more work to get done.

Phew. There sure was a lot to do.

I created an #accounts channel in our Slack workspace to collect all the conversations with customers, to announce our new customers and to share them with our team. We were about 20 people at computers seeing our dreams start to come true.

More on those #accounts conversations as well as details on pricing and negotiation and creating a Fair Billing Policy and selling by email to come.

Up next:

Very cool. I love math.

I enjoyed the inside look at launching. How lucky/good to make the transition to paid with such ease.

Reading these, I keep being curious about total users. I could imagine a reoccurring data point across posts that relates to that number.