Briefing the Executives

Running the EBCs. Finding a vision / reality balance. Selling a future through the roadmap.

Meetings! Waste of time. Waste of energy. Too much of life is spent in them and no one wants another. They sap morale. They interrupt focused time when you could be working on real work, not in dismal attendance so some boffin can feel in charge and make the team jump through hoops. Am I right?

Well, yes, sometimes. Maybe even often. No one says, gosh, I’d love another meeting on my jammed calendar. That would be perfect.

But let me ask you to take a deep breath here. Clear your mind, because I’m about to make the case that meetings — done right — can be a beautiful, fiercely efficient way to run a business. And meetings — done right — can be the most effective way to close deals and create breakthroughs to achieve objectives. Okay, clear?

I’d like to start with the basics. We’re humans. We’re at our core social animals. As much as we sometimes forget, we’re designed to connect, negotiate, coordinate and communicate face to face with other humans. We’re optimized for it. Our voices, gestures, facial features, memory structures and more all point to a species purposefully made to meet each other. It’s inherent in us.

So how do we do meetings right?

Meetings Bloody Meetings

I’d also like to remember that meetings aren’t new, and frustration with meetings isn’t new. Take a trip down memory lane with me.

From 1976, I encourage you to review this half hour (!) video by John Cleese called Meetings Bloody Meetings. Sure, it’s a corporate how-to video at its core. But I promise, it’s funny and entertaining. As a bonus, you will be funnier and more entertaining to your colleagues if you watch it.

(Intro: John Cleese, in bed with his wife, complaining about meetings. In his papers, his wife has found a court summons for speeding and reminded Cleese to be on time for a family commitment on the same day.)

“No, no, it won’t take long. It’s a court case, not a meeting.”

“Well, they’re all the same thing really, aren’t they?”

“What?”

“A lot of people in a room trying to establish what happened and why, then deciding what to do about it.”

“Nothing like each other at all. In a court you have rules, procedures, it’s all organized. In meetings, you just…meet.”

(His wife turns out the light as he yawns in the semi darkness. Transition to Cleese in a dream about being on trial for running terrible meetings. He learns 5 steps to better meetings. End.)

The 5 steps suggested in the video for having better meetings?

Plan — Decide on precise objectives. List the subjects to cover.

Inform — What is being discussed? Why? And what you want from the discussion? Anticipate what information and people might be needed. Make sure they’re there.

Prepare — Prep the logical sequence of items, time for each item, based on importance.

Structure and Control — Take evidence, then interpret, then action. Stop people from jumping ahead or going back over old ground.

Summarize and Record — Summarize decisions and record them with the name of the person responsible.

Hmm. That’s a decent list. Definitely better than no effort to run a meeting. Even some overlap with the process we used at Executive Programs at Slack.

Steps 1 to 3 we applied pretty much as stated, with some massaging for context. Step 4 though, we did not use. Having people jump ahead and jump back was often very valuable. If we cut off the exploration of a topic we cut off the chance to learn about it and include its lessons and context in our process. Step 5, we definitely used.

But wait. I’m jumping ahead now. Step 4 goes for writing too!

And We’ll Call Them Briefings

So how to resolve the tension between the fact that no one likes meetings but meetings are what we’re optimized to do? Our answer: reinvent meetings as Briefings.

No, no, it’s not a meeting. It’s a Briefing — an Executive Briefing. Reinvention happens all the time with good results. Convection oven? No. Air fryer. Mouth detergent? No. Toothpaste. Names are the hangers of meaning.

Working in Executive Briefings we had a mandate to create the best kinds of meetings, with strong preparation, execution and follow through. We didn’t invent the concepts. Many other companies also ran Executive Briefing programs. But we did pioneer the concepts at Slack and make them work for our team.

And to make it all work, we needed to collaborate with 3 key groups.

Slack Sales — Our teammates working in Slack Sales on large accounts, as well as their managers. They defaulted to be strongly supportive of doing briefings, because any time they could get with their customers’ executives seemed great, and getting time with the Slack executives seemed good too. No harm in looking good for the home team.

Slack Executives – VPs and C-level titled folks on Slack’s executive team who got sequestered in to help advance deals. They defaulted to mildly supportive of doing briefings, in principle, because they were all good team players. But they also remained cautious of any demands on their time. Did it have to be them? Did it have to take so much time? How could they succeed with their role in the briefing?

Customer Executives — VPs and C-level titled folks at Slack’s customers. They fell into 3 big groups with slightly different reasons for why they might care:

Line-of-business leaders (VP of Engineering, CTO, VP of Customer Service): They ran a large team at a customer. They wanted to know how Slack was relevant to their part of an organization and how it could help with their specific organizational goals. They could sponsor a deal (give a Yes) and often ended up as some of our best contacts.

Line-of-responsibility leaders (CISO, CTO, CIO, VP of IT): They ran a function at a customer. They wanted to know in depth how Slack worked and integrated with their organization and systems. They could block a deal (give a No) on security concerns or pricing concerns or technology vision concerns but rarely sponsored a deal.

Organization-wide leaders (CEO, CIO, CTO, CHRO): They ran a team and a function at a customer. They wanted to know how Slack could work for their whole organization and what it could do for them. They could both block a deal and sponsor a deal.

That’s all pretty abstract so let’s dig into some examples.

Michael Lopp was Slack’s VP of Engineering as well as being a semi-famous writer on engineering culture under the pen name Rands in Repose. We had lots of engineering focused deals on the boil at Slack NYC. We brought in Lopp to do a series of briefings with customers’ Engineering leaders at our Executive Briefing Centre. Lopp showed them how the Slack Engineering team used Slack. How he used Slack. How they could use Slack. He talked about the culture fostered by using Slack at Slack.

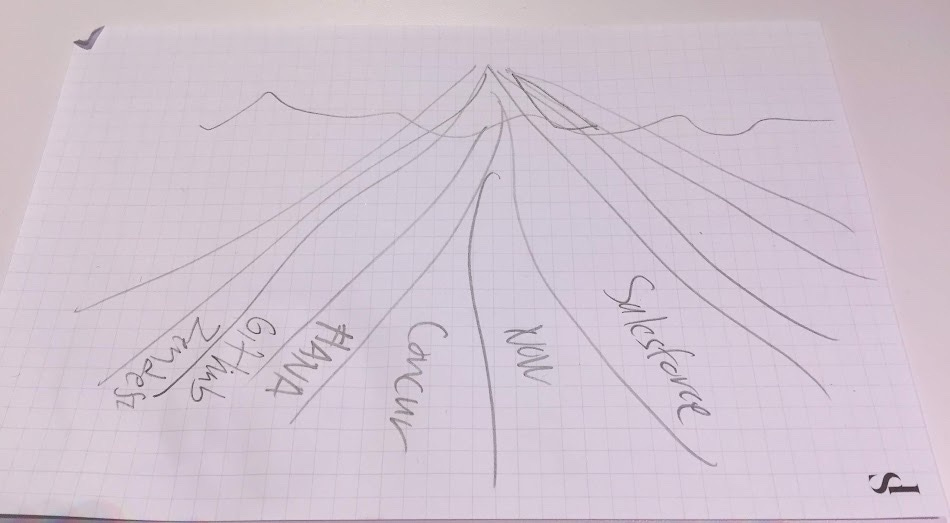

Ilan Frank was Slack’s VP of Enterprise Grid (our product for large customers). Those large customers grew in importance and wanted much more access to Slack’s leaders. They wanted insight into the product roadmap — when was their pet feature coming? We wanted to sell them on our future vision of collaboration. To join and serve both those interests we created a briefing series called Slack Product Roadmap and Vision. We ran it dozens, maybe hundreds of time. It used our roadmap to lead into showing how our vision came to fruition.

And of course, there was Stewart, Slack’s CEO, main spokesperson in public and boss. Everyone in all 3 groups above wanted to meet with Stewart — he was a star. And Stewart’s time was one of the most closely guarded secrets of Slack. As such, if we got a glimpse of Stewart time, we’d often create a briefing or series of briefings. We also reserved Stewart’s time for only the largest or most valuable customers’ briefings.

Sometimes the content and discussion of briefings was feature / function focused on releases in the next 3 quarters. Sometimes the content and discussion was much higher level and more strategic — How could Slack enable an international acquisition? How could Slack improve employee retention? How could Slack activity visualize and provide insight into communication pathways in an organization and then correlate those pathways onto team performance? Sometimes it was a blend. It all depended on the objectives we sought to achieve with a customer.

No matter who we ended up working with or what we ended up discussing, our goal at Executive Programs team was to run our process. People got tired of hearing about our process, but it worked and ensured a scalable, predictable, repeatable experience that positioned all 3 of our key groups to succeed.

We always started out gathering lots of information, consolidating it into one place, reviewing it as a team, doing a pre-briefing, doing a walk through, running the briefing, then doing a de-briefing to improve, debate and decide on next steps. Rinse and repeat and improve and let’s go.

Slack Sales Hated our Process

I’ll just say it at the start and get it out of the way: the key people we had to work with — #1 of the 3 groups above, Slack Sales — consistently kind of hated our process. Maybe hated is too strong here? Chafted against it, defintely.

To them, I heard it felt cumbersome, painful, onerous. Filling out forms? Putting some thought into objectives? Specifying outcomes they sought to achieve? Specifying outcomes their customer sought to achieve? Oh man, no joy. Couldn’t they just set up the meeting themselves?

And sure, they probably could go around our process. We were an internal service provider without much of a stick. Our Legal team were internal service providers too but no one could go around them because that’s how deal terms got finalized. Our Revenue team were in the same boat — no one could go around them because that’s how pricing got concluded. We didn’t have a similar consolidated power. We had to use much softer tactics.

Mainly, I had to create relationships with our sales managers and Account Executives. I had to stay on top of deals as they got to the right stage for a briefing, and what executive(s) we could use to move those deals ahead. I needed to have success stories to tell our sales team about Executive Briefings we had done, to give them ideas and to connect our work to the effects on a deal. In short, I had to sell our internal team on using our internal services.

With some Sales teams this proved easy. They welcomed the help. They often came from places with strong executive briefing programs. Or they did a briefing with one customer and then wanted to do the same with all their customers. Hot damn.

With others, it was hard to sell our services. They felt a sense of ownership over their deals. They didn’t want to share. They didn’t want things happening on deals outside of their purview. They didn’t see why they needed to follow our process. Couldn’t they just DM Cal and get him to join a meeting with their customer’s CTO? Sure, give it a try and see how it goes.

The good news is I never felt threatened when folks didn’t want to use our services. We had no shortage of demand. Following our process meant the sales managers were happy, the assistants of Slack’s executives were happy. And the results started to roll in positively too.

Slack Sales Eventually Loved our Results

So though our process was a bit of pain for Slack Sales, the other 2 groups of folks we worked with all the time — Slack Executives and Customer Executives — loved working with our process. That was mostly because they had people to do all the painful parts. Then they got to experience the tight, objectives-driven agendas, the pre-briefed speakers, the nice touches like catering and swag.

For Slack Executives, if we ran our process well, they could be confident that when they showed up they would be set up to succeed in their role. They had gotten a written and in-person pre-briefing. They knew the talk track expected of them. They knew who they were meeting with from some background details on all attendees.

And right, the results. They were very good. Slack Sales, once they got through the process, loved the results. And of course, we tracked them as part of our process. Here are the headlines:

Having an Executive Briefing meant a deal had a 77% win rate, versus a 33% general opportunity win rate.

Each year our contribution to the business grew and in my last year that meant we touched deals worth $94-million in annual contract value.

There were big, standout wins and many steady, smaller wins. I’m happy to be able to say the team I worked on did good work daily and it paid off in the big picture. We did 500+ briefings in my last year with top customers like IBM, McKinsey, Apple, Oracle, Nike, Lockheed Martin and Verizon.

This all feels a bit braggy now, so I’ll wind it up. It was great work to have and I was lucky to do it. I was even luckier to work with a great team around me.

I think if my experience doing Executive Briefings taught me anything it’s that competitive advantages are often hiding in plain sight and look like hard work.

Taking an essential business process people generally overlook — meetings, in this case — and doing them as well as they can be done can be a competitive advantage. Being thoughtful and expecting execution at a high level over and over again can be a competitive advantage. Having the luxury to spend the time on the details and to get the process right can be a competitive advantage.

So meetings bloody meetings might be a popular sentiment and an easy label to avoid engagement or improvement in something we’re built to do. But in that frustration lies an opportunity and a reinvention of meetings to Briefings.

Up next: Innovation Tours — Harnessing our story. Finding a new decision matrix. Building a culture of innovation.

The 77% win rate stat is wild. That kind of conversion proves process matters more than people admit. The friction Sales felt with your forms probaby actually forced better qualification upfront, which is why outcomes improved. I've run similar programs (tho nowhere near Slack's scale) and that pre-brief step always gets pushback but it's where the real prep happens. The exec who shows up unprepared tanks the whole thing.