Gentrifying Slack With Radio London

Moving up in the old world. Coming to you live. Making my mistakes. Updating my priors.

Let me circle back to tell the full story of Slack London. Our first employee on the ground was Rav Dhaliwhal. But Rav and I first met in Dublin. He contacted me out of the blue, saying he’d be in Ireland for work. He worked at Zendesk doing something called Customer Success, should we get together?

Yes, we should. And yes, we did, at our Dublin office a few days later. We talked about his experience working with customers to help make them successful with their software purchases, the emerging field of Customer Success. Turned out that when your software product got used throughout an organization, every day from log on to log off, you had make sure your customers used it well. Amen. In short, we hit it off.

It happened that pretty much at that moment we were finding Slack needed Customer Success. Sometimes customers demanded it. Sometimes we suggested with varying degrees of insistence on it. In either case, we needed to ensure that once a customers signed up for Slack, we got to teach to them to use it, use it well and then renew for a lifetime (i.e.: 2+ years in software). So my meeting with Rav proved to be perfect timing.

A few months after our first meeting, Rav joined Slack and started both Slack London and Slack’s Customer Success practice from his kitchen table. He quickly learned about our product and our customers and taught Slack about Customers Success. Prior to Zendesk, Rav had worked at Yammer, Salesforce and IBM. He arrived with a consultant’s background and fancy, capitalized, proper-sounding names for the things that seemed like exactly what we need to do: Needs Analysis, Success Criteria, Rollout and Migration Plans.

Slack London then quickly found real office space in a WeWork tower in Spitalfields, near Bishop’s Gate. Trouble was, this location became the office no wanted to work in. It wasn’t unpleasant or dangerous, but it wasn’t terrific. It was just hard to get to and London was a sprawling metropolis built on a plan of many villages. The commuteless lure of the work-from-home life proved too strong.

The upside to the WeWork space was that we had a corner office with lots of light and glass walls and a view of the reflective cliff faces of similar office towers that surrounded us. The downside was that our glass walls provide zero audio or visual insulation internally, so any conversations from neighbours penetrated our fish bowl, and vice versa.

At the centre of the floor, call booths provided some sound-proofed, padded-wall privacy, if you could book one. The call booths quickly got booked up and people generally stayed home to do their calls. Since calls constituted a large part of the job, the office stayed mostly empty.

That first Slack London neighbourhood felt like a definite moment-in-time highlight for me too. Walking Spitalfields felt like late gentrification. The old market remained and butted up against the new — gritty vendors with temporary tables set up in front of the Lululemon boutique. An Aga showroom displayed ranges costing tens of thousands of any currency, a lifestyle promise of leisure, health, abundance, a modern English countryside fantasy. But reaching their showroom meant stepping over a man with dreadlocks strumming a guitar, his case open for change.

To serve and drive our growth, we quickly created new openings for new people to join Slack London. Rav pulled in Liv, who he’d worked with before, to round out our Customer Success capabilities. She was excellent and salty and very capable. I’ve mentioned how Vic joined Slack from Google and acted as our first Account Executive in London. She capably ran all our UK customers of any significant size (what we called “Enterprise” at the time). Everyone has only three letters in their name until Chris joins as a Solutions Engineer. Now where would we put them?

Moving Up in the World

I’ve also mentioned before that it felt very much like Slack entered its teenage years as we opened our London office. We had decided to be a Sales team and go all in on a really big aspiration. Right-o.

Now we had to do it, and that proved to be fraught with complexities and awkwardness, some searching, some flailing. We didn’t want to lose what we had but we did want to grow into something new. We had fears of what we might become.

Jobs on our Sales team grew more complex and specialized to improve on the depth of expertise we could offer and to free up Account Executives to pursue larger sales opportunities. Solution Engineers helped with the technical and security details. Customer Success Managers helped with rollout, adoption and use. Everyone started using abbreviations for the more specialized roles: AE, SE, CSM.

Did it work? We definitely gained in the depth of expertise we offered to our customers. Our specialists had more specialized capabilities that our customers definitely sought from us. And it proved easier to recruit new employees because now our internal structures and roles reflected those of other software companies.

As a tradeoff, our customers lost the simplicity of having a single person they could contact to solve their problems. It felt like our own gentrification was underway. The edges and corners of our differences got sanded away for efficiency.

The customers commensurately grew as well. The BBC signed on. The government tax collection service, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) signed on. The Financial Times signed on. The British Museum signed on to use Slack and agreed to let us use their name for some joint PR. We found ourselves moving up in the old world, climbing the high tea status ladder in London, helped by strong momentum from the Elgin Marbles.

I went to an event at something called Silicon Roundabout (a name no one but bureaucrats and promoters used) and every tech company told us how they used Slack, keen to highlight their custom bot or integration. This customization of Slack for their own purposes made it incredibly sticky. A combination of the product’s many options and the frequency of its use made it a playground for anyone with modest technical skills. They made it their own and felt a sense of ownership over their creations.

Not everything went smoothly though. We did a long sales cycle with British Petroleum and, after many turns of redlined Word documents from their lawyers and security audits and other attestations of our worthiness, they didn’t officially sign on. Over a thousand of their employees paid to use Slack though. They used it for hours every day, then expensed it at the end of every month. But they didn’t sign on, the truism that “time kills all deals” proving true once more.

We did another long sales cycle with Tesco who were in the same situation — lots of people using Slack, paying for Slack, yet no official blessing. They seemed content enough to let the current situation run on at its steady state, and that status quo seemed better for us than forcing a year-long internal Vendor Evaluation process from them. Maybe eventually something would need to be done.

We started to learn how large organizations operated on their own timelines and with their own incoherencies. Perhaps it was an English thing to just keep calm and carry on with such inconsistencies? I’m not sure. Such was life. We pushed on.

Coming To You Live

As our business in the UK grew our team grew, and we quickly outgrew the WeWork office that no one visited. We sought out another office, one that matched our ambitions, matched our desire for prestige and status and our growing capability to pay top-dollar rents.

Touring empty For Let office spaces, I got a chance to see our office options first hand, on a day of tours chaperoned by commercial real estate agents. They started us with some dodgy options, testing our reactions. Gradually the options improved from under construction lofts to full gleaming floor plates.

We reviewed a half dozen options and then met our match, a former BBC Music studio called Yalding House that proved simply too gorgeous to resist. Walking the empty space I could perfectly imagine the emerging version of Slack and Slack employees living in it, thriving in it and fitting in. It felt foreign yet near, gauzy and plausible all at once.

Life at Slack existed at the time in a few different dimensions of time, all of them changing very quickly. Assumptions needed to be updated to keep pace with a newer and newer reality that lived somewhere between the versions of today and an imagined tomorrow. Our new Radio London office space was one of many holy crap moments for me where I glimpsed the further future.

I had flashes of concern for the price that our reach for status would cost. Surely this was beyond our means, no? Much more space than we needed? Too fancy by half? I still felt rooted and responsible to our modest beginnings, getting things to just work. The urgency to make the most of every dollar. And yet.

On those office tours I could see our aspirations come to life, and how an office could symbolize those big imaginings, could project for employees, press, visitors, customers, etc. the class of polished outfit we intended to be. Perhaps we already were? In a world where no one knew anything and everyone was trying to thin slice their way to some sense of what was happening, who was important, what they should bet on, an office address and fit out could provide a powerful clue.

We got approval for the space and cost. The internal enthusiasm built. The fit out went ahead: construction, furniture, decor, signs, details. If we were going to go for it, we decided to go for it all.

The meeting rooms got built out and named after a roster of famous British musicians: Bowie, Rolling Stones, Queen. A dark hallway in the interior featured a rainbow lighting scheme. Walk its length and you passed the full spectrum: ROYGBIV. A black spiral staircase led from our reception to a top-floor mezzanine level that housed our Executive Briefing Centre. Executive Briefing Centre? Yes, more on that later.

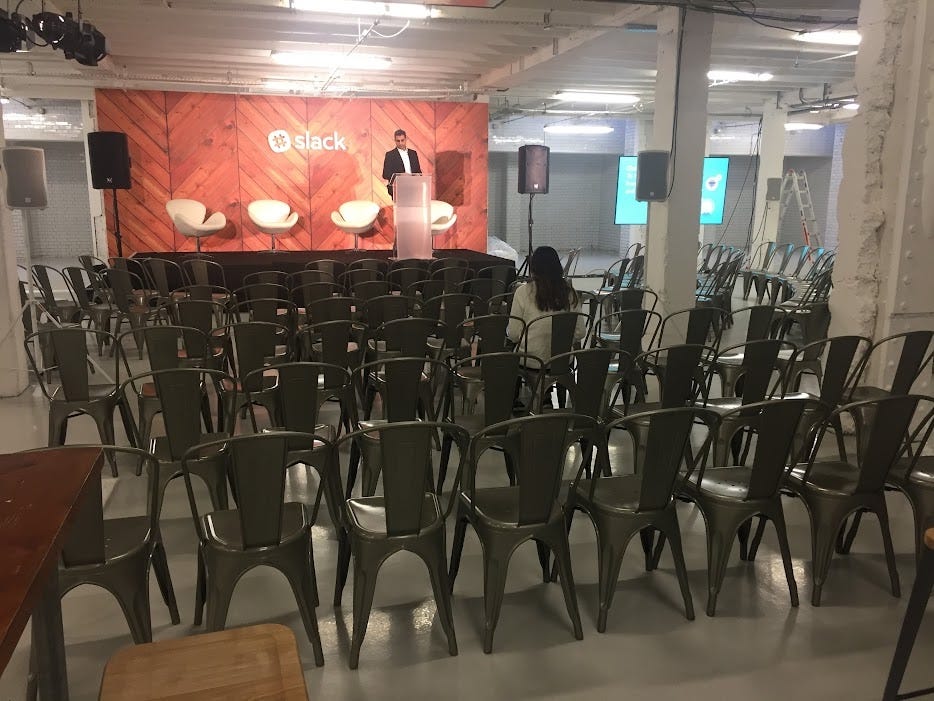

We hosted an opening party and invited customers and prospective customers, employees and prospective employees. Slack London now occupied the top 2 floors above Great Portland Street, connecting the thoroughfares of Oxford Street and Marylebone. A rooftop deck surrounded us on 3 sides with views of the BT Tower, the London Eye, the Gherkin. In the lobby a sculpture made of vinyl records showed the audio wave of the last thing said on-air from the building’s former BBC studio tenant.

A listening room lived off the main lobby in another nod to the prior tenants and the building’s former service as the home for BBC Music.

A week after the opening party, I again visited the new Slack London office to do some work and I could see the change: everyone wanted to brave the commute to work in this office. It made people feel good to be there, to be part of Slack, to do their daily tasks in a lovely setting.

Making My Mistakes

Looking back and telling these stories it all seems like a continuous progression, like maybe we knew what we were doing. That’s the nature of looking back. But in the daily moments flying from Dublin to London and back, it felt more bumpy.

To start, I had doubts about my own capabilities. I was in the weeds and failing to get to a high point to stick my head up and check the view. I was unsure what to make of all this change at this pace. I was working as hard as I knew how and yet there always remained more to be done. What was most important?

In my haste and inexperience, I made mistakes. Some of them I saw in the moment. Some of them I can see more clearly reflecting back on those days. Here are three that particularly sting in recollection and hopefully provide some guidance to anyone in a similar situation.

First up, a mistake in etiquette. Our newly minted global sales leader, and my new boss, Bob Frati flew over to visit. Bob and I interviewed Account Executive candidates together. He had sent me a book to read called Who: The A Method for Hiring. We were implemented a new candidate selection method called Topgrading that used an extensive process to group candidates into A Players, B Players, etc. I got the impression that Bob was pleased with the folks we had in roles, and he also wanted to change how we brought in new people.

I remember Bob and I were in an interview with an unremarkable candidate for an Account Executive role. We’d decided beforehand that Bob would lead the conversation and I would take notes. He wanted to train me on how to lead the interview and I needed some practice. Right on. I was keen to learn and wanted to do a strong job with my part.

The three of us — Bob, me, that candidate — sat around a small table. Bob had the candidate’s resume printed and was leading a chronological interview. I was taking notes on my laptop. The purpose of “the chrono”, as we called it, was to review all the relevant roles in a candidate’s work history, from oldest to most recent, and tease out what went well (achievements) and what needed work (development opportunities) in each role. Then we probed to find patterns. The key phrase we used for each role was, “What will your manager say when we call them as a reference?” Not, the hypothetical “…if we call them…” but the definite “…when we call them…”

As the conversation progressed I got the sense that my typing was distracting Bob. After a few minutes he stopped the interview and asked me if I could take notes with pen on paper. Okay, I could do that.

That moment felt like a small mistake and I’m not sure anyone else in the room would even remember it. But it felt to me like a mistake of misunderstanding, like a mistake where I positioned myself to Bob as a person without nuance, insensitive to the context of a meeting and obtuse to how my actions affected others. It felt embarrassing to have the interview stopped and to be corrected.

The second mistake happened also with my new boss Bob, and was also a misunderstanding. But it was less acutely a moment, and moreso a disconnect about how we evaluated candidates and selected people for roles.

With Bob newly in the job, how we ranked the information we gathered on a candidate also shifted. We wanted people with a proven track record, people that had done the equivalent job elsewhere who could be brought in to do the job at Slack. We started to focus about sales quotas, target attainment, on-target earnings.

I got that we were shifting how we hired but I didn’t totally get what that meant to our hiring, and I was slow to change. I was still hiring for the past and present, for the Slack I knew, where I had built the hiring process, where we weighed more heavily the candidates’ performance in the application process than their experience. I was hiring for what I’ll simplistically call character fit over proven track record, because we had thought we were hiring for pretty unique roles and had to find candidates who combined sales acumen with conscientiousness.

Sure we looked at candidates’ track records, but we had succeeded by hiring for character first, and not just transposing someone’s success elsewhere to what they could do at Slack. We talked about wanting ‘Slacky’ people who could do Sales. This emphasis shifted with Bob taking over. Now we wanted Sales people who could do Slack. We wanted folks a bit more mercenary than missionary.

And in hindsight I would have to say he was right to reorient us to track record of success. We’d been successful to that point, but it was another very acute reminder that what got us there wouldn’t get us to the next stage.

We started hiring top performers away from B2B enterprise software competitors — Microsoft, Google, Dropbox, etc. Bob understood the sales organization he had to build. He had seen it done. To be able to scale up and hire as many sales people as we would need to hire, we had to orient toward their proven track record, that scaled and could be uniform. A hiring manager’s judgement call on character fit? Way harder to replicate and standardize and manage.

Did this change mean we didn’t hire great people? Not at all. Going through the list of new employees that joined Slack’s burgeoning sales organization as we opened our Radio London office, I see some of the best folks I ever worked with. It felt like a shift, and the folks that came in felt so strong that it seemed to prove the shift was working.

Yes, it certainly meant our culture was changing too. We had changed our name to Sales from Accounts. Now we started to build a Sales team that could compete with the other top sales organizations in the software world.

(And I don’t mean to beat myself up too much here, retelling these stories of mistakes. We were a teenage company. It was the time to make mistakes!)

The third and most prominent mistake I made during this shift in our hiring approach was in advocating for an internal candidate to lead our UK team. Bob and I had discussions on what kind of person might be a good fit in the role. One of our Dublin employees was a force of nature. They were doing their own job and more. I knew they were ready for a bigger challenge, I just hoped it would be with Slack. I put them forward as a candidate to relocate and lead our London team.

But they didn’t have experience leading teams, or living in London, or leading Sales in the UK. I recognized those limits on their candidacy but I thought they could do the job exceptionally well anyway. Those gaps in experience were challenges they could overcome. They were through and through a terrific culture carrier and a dedicated contributor. I believed they could do the job, learning to do it as they did it, and tackling all the unforeseen things that would arise outside the job description. Again, I was still hiring for character fit — someone ‘Slacky’ that could do sales leadership.

Their candidacy was not moved ahead as an option.

That moment really highlighted for me that I had a mismatch with Bob on what we were seeking in candidates. I was still hiring people for the jobs we used to have, for the company we had been, and based on their track record at Slack. He was hiring people for the jobs we were going to have, and the company we were becoming and their track record outside of Slack.

One of those perspectives was obviously better aligned with time’s arrow, and it proved clearly to be his.

Updating My Priors

As they say in Silicon Valley, I had to “update my priors” to match our new reality. And that reality had snuck up on me and sped past me before I had noticed. I had missed the memo that I had to do different parts of my job in a few different streams of time.

Do I regret these mistakes? Yes. If I’m honest, I do feel some regret about them. I wished I hadn’t made them. But I did. And there are more too.

I showed my own inexperience in these lessons. In doing so, I stumbled at the start of a new, unwritten game I didn’t know the rules to. This was Zork without the user guide. This was executive sales management and I was trying to learn to play while playing.

This game involved status and judgement and ability to deliver results. It involved inferring the smaller signals of belonging and power. I was a noob, learning fast but certainly no threat to set the high score.

I had been in charge of hiring and now I was only a contributor to hiring decisions. I had set the rules for hiring and now someone else had set new rules that I needed to learn. We had operated in our own bubble in EMEA and now we were being pulled into conformity globally to reach scale.

In digging a bit deeper here and trying to unpack what I felt like was really happening at Slack at the time, I don’t want to leave the impression that I was against any of the changes. We had to change.

I believed then and I believe now what we repeated internally: what got us here won’t get us to there (meaning, the next level of size / scale / success). I don’t feel particularly conflicted or like I was coopted. I bought in and supported the changes and was on the bus. I just had to figure out how to get on and play my part.

Did we recognize the bargain we were making? Yes. I think we did. We were a venture-backed software startup with a multi-billion dollar valuation. We had to grow our business to justify it. Growth was our primary job. There wasn’t time to waffle.

The classic thing to wistfully say here is that something was lost along the way. Something lost for financial gain. Some nostalgic element of Slack had to be sacrificed.

And something undoubtably was lost: our naivité, our bubble of independence, the quaint way we thought we could question orthodoxy.

But it’s not like those were things we wanted to hold on to more than we wanted to grow. We wanted to build Slack bigger and strive to reach our potential. We just also wanted to retain some germ of what made us special along the way. And I think we did in a deeply pragmatic way.

We got over ourselves, and any compunctions or doubts we might have had, and we enjoyed the ride. And what a ride it proved to be.

Up next — How I Replaced Myself in Europe: Prospecting candidates. Moving upscale in Dublin.

I enjoy reading about your personal “mistakes” and evolution amidst all the corporate growth. In a total aside the “where’s your head at” art - is the name of a song written by my cousin Felix of Basement Jaxx. Just had to throw that in there :)