Becoming a Senior Technology Strategist

Making up the job as we went. Being the Slack man. Fumbling towards legitimacy.

Let’s start with the basics. Maybe you are and maybe you aren’t thinking what I was thinking as I started my 5th job at Slack. So here it is in either case: a Senior Technology Strategist? Is that a real job? It doesn’t sound like a real job.

When I first found out about my new title, it sounded pretty soft and nebulous. A bit like a Brand Ambassador or an Influencer. Pretty bumpfy and frothy. The job title equivalent of too many pillows on the bed. A symptom of the times of zero interest rates and easy money for startups. Not essential like Engineering or Sales or HR or Marketing. A luxury and an indulgence. Probably the first to get cut in any downturn.

At the same time, since it all felt pretty undefined, the job presented itself as open for me to define what it meant — through intention, then action, then results. No one else at Slack was a Strategist or had ever been before me. Hardly anyone else knew what to do with my job (with the possible exception of my boss Marnie). So I realized I got to figure out what it meant to do the job and put my name on it. That sounded fortunate and familiar because it’s pretty much the same as I’d done with all 4 of my prior jobs at Slack.

No one had done Marketing before me at Slack. No one had done Sales. No one had been a Sales Manager. No one had opened a new office. So this new job linked up to the chain of my prior jobs as one I had to figure out as I did it.

And when I put it that way to myself, everything felt more substantial and promising. And I felt pretty keen to get started.

Making Up the Job

At the start, the job focused on executive briefings with some public speaking sprinkled in. I introduced the job and team and Marnie in meet the new, new, new, new boss. That hybrid job I had started lived in a specific time and place — in Dublin and Europe, before we relocated back to North America.

Then once we’d landed back in Vancouver, I got started on the intended job. It’s the job I did for the longest at Slack and it’s the last job I did at Slack. And, as I did the job, I found out what it could be. The job grew. By the end of the first year, the job had become like a portfolio of activities, all focused on moving ahead conversations about Slack.

Those conversations converged into 3 types of work:

Executive Briefing Centre (EBC) engagements — Working with our account teams to build agendas to advance conversations with our customers. This was about 50% of my job.

Investor and Partner engagements — Working with our investors like Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), Google Ventures and Softbank and our partners like ThoughtWorks, Bain and Accenture to introduce Slack to prospective new customers. This was about 20% of my job.

Innovation Tours — Working with professional education providers, embassies, chambers of commerce and government teams to host visits to Slack for their touring groups and introduce them to Slack’s culture. This was about 30% of my job.

I’ll spend a bit more time in the next few posts unpacking each of these 3 kinds of work because I think they each offer their own lessons about where Slack existed at the time in its development, how business worked behind the scenes and what software companies can do to grow.

For the rest of this post I’ll try to unpack the common elements of my job that persisted across all the work I did.

Being the Slack Man

That’s what people said to me as I performed my job, “you’re the Slack man.” I heard it enough times in all 3 parts of my job — working with our account teams and customers, pitching at a16z’s EBC on Sand Hill Road, hosting an innovation tour of 28 executives from Fujitsu — that I gave up my resistance of the label and embraced it. Okay, I could be the Slack man.

I never talked about being the Slack man with any of my peers. I hardly dared to even name it to myself. But that was the main role I had to play for our business.

And if I was going to be the Slack man, I needed a uniform. My friend Darren used to say, “clothes are costumes, costumes are symbols, symbols are powerful.” So I tried to take that cue from his theatre background and embrace it.

I had a purple jacket made. I also had some dress shirts made. When the tailor asked me if I wanted my personal initials on the cuff I declined, then asked, could I have anything on there? Anything that’s 3 letters, I learned. I had OMG embroidered to peak out and remind me to keep my sense of wonder. I wore my Slack socks.

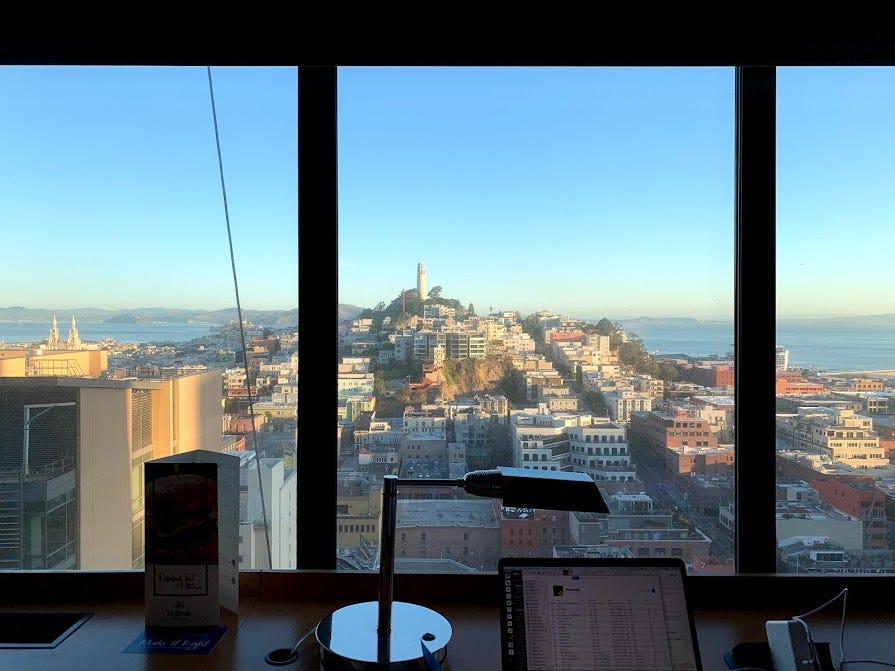

Wearing a uniform made packing simple for all the travel I had to do as the Slack man, and I was into that kind of simplicity. I stayed at the same hotels if I could. They had good locations, reliable beds and decent gyms. I ate at the same restaurants. They had good locations, reliable service and healthy options. The Slack man had to take care of himself to keep going.

The thing I never anticipated about business travel is just how much time you end up spending on your own. You have to get good with your own company because you spend a lot of time alone. I started to collect and read the new editions of the 75 Maigret mysteries from Compass Books at SFO. I passed through with enough frequency I could order them and pick them up within a week or two.

One of the best parts of Slack man life on the road proved to be the chance to explore the destinations. In London, I had established a habit of walking from the office to my hotel each night. As I kept exploring cities, I found reservations for one at restaurants simple to get. Anywhere had a single seat for me and I had my book for company.

I know I’ve used this metaphor before, but it’s perfect here as well. The Slack man life felt like I was a stone skipping across the surface of water, of work, of Slack. I had a travelling identity as the Slack man. I had a home identity back in Vancouver. I kept on keeping on.

On the road I got to connect with specific customers with their account teams. I got to work with our executive team and set them up to succeed with customers. I got to represent Slack to the outside world in small gatherings. I trained myself to say ‘PRAH-sess’ as the Americans say it instead of ‘PROH-sess’ as Canadians do. The Slack man had to blend in and not offer any reasons for suspicion or foreignness.

Sometimes our goals were best served with me back of house, formatting the data of guest lists to get badges printed or updating a CRM or coaching account teams to narrow their agenda, to prompt an executive for a specific strong talk track, give them stories of other accounts they could learn from. Sometimes I was front of house facilitating a discussion, touring guests through Slack’s offices, introducing our executives and building on their answers to questions.

It was fun and frustrating at times. It was hard and easy at other times. I enjoyed pretty much every day of its contradictions.

Fumbling Towards Legitimacy

In the chapter on gentrifying Slack with Radio London I wrote:

In a world where no one knew anything and everyone was trying to thin slice their way to some sense of what was happening, who was important, what they should bet on, an office address and fit out could provide a powerful clue.

I think that’s right about its topic — an office address and fit out — and far beyond too. It’s right about all kinds of things in our world. It’s right about software certainly. What to buy. What to align with.

Way back when we got started, when we didn’t sell saddles and marketing was something we all worked on, I learned that we had the chance to create a new reality for our customers:

If anyone had asked me before my Slack journey whether beliefs drove behaviours or behaviours drove beliefs, I would have answered that it didn’t really matter in marketing. It could be either.

But for a new product, I wanted to work on changing people’s behaviours, not their beliefs. To change their behaviours was easier and faster. I didn’t have to convince you a Big Mac is good for you or a smart choice. I just had to tell you about it when you’re hungry, and to have a restaurant nearby that can serve it to you quickly, reliably and cheaply. You can buy something whether you believe in it or not. Then once behaviours are changed, the human intolerance for cognitive dissonance acts to change beliefs. Maybe that Big Mac isn’t so bad in a pinch. At least, that was what I believed before Slack.

What we were proposing to do was the opposite: to change people’s beliefs so that they changed their behaviours. It was very risky. We needed them to believe a better way of working was possible to try our product. They already communicated, so what if they could communicate better?

Now, as the Slack man, I had the chance to refresh our vision of how work worked and give people a story to believe in.

But me telling you this as a tight, coherent story masks how we got there. It wasn’t fast and it wasn’t clear. It was haphazard and eventually got headed in the right direction. I’m compressing that flailing to create simpler through line of why I could be the Slack man. I had been preparing for it since I started at Slack and just luckily stumbled into the role at the time the role got created and needed someone.

It meant I had already been to a series of a16z briefings at the Rosewood London, where I held the front door open for Kate Moss and she said, “Tah” and then I had descended to the basement ballroom to tell HSBC and Standard Chartered and Barclays and Lloyd’s about Slack. And I could draw on all those experiences to help myself and the folks I worked with make sense of the moments we shared.

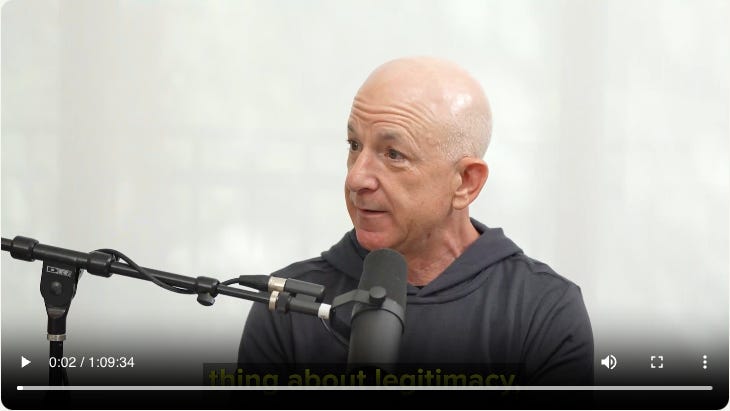

“Legitimacy comes from selling the future,” says Steven Sinofsky as he provides a video and written crash course in how enterprise software has gotten sold over the past 50 years. And Sinoksly should know! He ran Windows as part of a 20+ year career at Microsoft, and he had to learn to sell the future (just as I had to learn to sell the future) as part of their executive briefing programs.

Microsoft had an Executive Briefing Center where we would host CIOs all day, and all the Microsoft product people would give talks to convince these buyers that you had a strategy and a master plan. I went to the first one of these meetings, and I remember thinking, “This is the dumbest thing I’ve ever been to.” Because I came in, ready to do a big demo to talk about the product - “Here’s Office 97, it’s great”, and all they wanted to hear about was my Ten Year Plan.

And, here’s the best part, you get rated for your presentation. And I got crappy ratings. Steve Ballmer, who was running the enterprise sales force, told me point blank, “This cannot happen!” This was a hard lesson to learn. Because, as the person who shipped the product, all you can think about is this mountain you just climbed to make that moment, and that demo, and that feature, possible. But all they want to hear about is, “What is Word Processing going to be in 10 years?”

So what was Slack’s vision of how people communicated in 10 years? That’s what we needed to figure out and that’s the question I (and many more amazing people) would spend the rest of my Slack career working on.

Up next — Briefing the Executives: Running the EBCs. Finding a vision / reality balance. Selling a future through the roadmap.