Meet the New, New, New, New Boss

Getting to know Executive Programs and Marnie. Cramming to the end in EMEA. Learning to do by doing.

After 4 years at Slack, reporting to Stewart, then Allen, then AJ, then Bob, Marnie Merriam became my 5th boss and, I think they would all agree with me, my best boss. In many ways she became my first real day-to-day boss — a manager I worked with tightly on tasks, who knew my job well and who did 1-on-1s with me (instead of the other way around).

And, at the same time as Marnie became my boss, I became the boss of no one. I had no direct reports. Zip. Zilch. Zero.

For the first time since I started building teams at Slack in October, 2014, I just had me to manage. I just had to do my job. I didn’t have to worry about whether my team did their job. I didn’t have to solve anyone else’s problems for them or coach them to find their own solutions. I just had to solve my own problems and do my job as well as I could.

And right away, I felt a terrific lightness with my newfound lack of responsibility. And I felt some guilt at my terrific lightness. Was this too easy? I had habituated to carrying more responsibility. I felt like I should still carry more responsibility. So much remained to be done! And responsibility equaled importance so could I still be important and have an impact?

I wanted to find out and I had put my responsibility down to do so. That change meant I needed to find new ways to conduct my days — way fewer meetings, next to no one contacting me to see what I thought about something. Big changes on the daily habits. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t wander for a small bit of time in those days, finding a new cadence to follow. But then, pretty quickly, work all felt much easier and like maybe I wasn’t doing enough of it.

So what did I do? After a bit of discovery on the job, I realized that just because my role was narrower didn’t mean it didn’t also offer a ton of depth and opportunity for impact. I tried to refocus and do the best work of my life and put my name on the job I did. I pushed my rediscovered capacity onto the essentials of the job and went hard on those essentials.

Essential step 1: get to know the world of Executive Programs and working with Marnie.

What’s Executive Programs?

I know. That’s was my first reaction too. What’s this Executive Programs business? So let’s zoom out for a second and take a quick tour.

By this time in 2017, the Slack sales team was getting close to 150 people globally (a rough estimate on my part, maybe it was 175?) in 6 offices: San Francisco, Vancouver, New York, Dublin, Melbourne and Tokyo. That growth we’d seen in 2 years in Dublin going from 3 to 62 people? Apply that same growth rate to our sales team and you can see how we grew so far and so fast. Slack had been busy already and the rate of growth on the Sales team was about to increase.

As Slack’s sales team had grown it had also gotten more specialized. Direct sales roles had gone from general to specific. Markets got segmented by customer size and geography. New sales support roles slotted in to help our sales process. Now we had folks in legal, revenue management, solution engineering, customer success. Selling Slack had become a team sport, especially with large customers.

We’d also brought on lots of folks with significant enterprise software sales experience. Bill Macaitis had joined as Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) from Zendesk and Salesforce, and Bill strongly advocated for the creation of Executive Briefing Centres (EBCs) to connect with enterprise customers.

EBCs were basically fancy meeting facilities dedicated to hosting executive teams. Sometimes that was a cross-functional single-customer executive team, the CEO, CTO, CISO and VP of Engineering from Airbnb for example. Sometimes that was a single-function, multi-customer group of executives, the CIOs of retailers like Walmart, Target and Nordstroms, for example.

Those fancy meeting facilities were lovely, sure, but what really made the EBCs work was the team behind them — the Executive Programs team. The team I’d just joined. That was us.

We worked as a sales support function, helping sales teams engage their executives, building small events to achieve specific objectives, making it all work. Most of that work happened behind the scenes with preparation and logistics — what I came to think of as back of house from a restaurant analogy. Some of that work happened with facilitation and hosting — front of house. In my job, I found I had to do a little of both.

Executive Programs also ran a few more things for Slack — and we’ll get to those. But the core of the work lived in the Executive Briefing Centres. We knew we’d been successful once folks on the sales teams started talking about ‘doing EBCs’ with their customers as a way to get significant advancement. You should do an EBC, they’d say.

Getting to Know You

Running Executive Programs for Slack was Marnie, my new, new, new, new boss. Marnie was bright and caring and compassionate. She had deep knowledge of the Executive Programs world I was just getting to know, with years of experience working in and then creating similar Executive Briefing programs at other large software companies. She was both reliable and delightful at once, spontaneous and consistent, a rare and charming combination.

I had none of the experience she had and she welcomed me and taught me. It felt like I knew Slack and she knew Executive Programs. So we combo’d up.

The first thing I had to work on was getting to know the new-top-me world of Executive Programs. Marnie oriented her work towards process and loved to get into the details. I had a lot to learn on the big picture of how our work fit into the organization, and then how all the small pieces of our work got done. Salesforce reports, searches and account tracking all gradually became my friends to run the processes. At the same time, I had to create relationships with our sales teams to get to know our customers and find the best ones for briefings.

A second thing I could work on presented itself pretty quickly — public speaking with groups from 6 to 600. Front of house work. Repping Slack to folks who might be interested in Slack.

Closer to the 6 end of that range of folks, some of our venture capital investors ran executive briefing programs too where they showcased their portfolio companies to prospective customers. I could lead those in Europe. We got invited to conferences. I could do those and speak and glad-hand and be the Slack man.

Cramming to the End

Our investor Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) set up briefings in Berlin and I went to meet the CIO of SAP. It was an illuminating first experience.

Top tip, if you meet a senior executive (or anyone you want to have an impact on, really): do some prep. Get to know them. Understand their personal context at their current job. Are they pushing a change agenda or stabilizing things? Cutting costs or expanding? Were they an internal hire or brought in from an external search? Where did they work previously? How long have they been in the role? What education did they pursue and how might that frame their worldview?

Sure, sure, I know you would never show up for an important meeting without prep. You would totally do that research. Right. Except. That’s not what I saw consistently happen.

I kept seeing folks from other a16z portfolio companies meeting the CIO of SAP and it became very clear very quickly they had not done much if any prep work. So just do it. It’ll be valuable to you whether you use it or not and it will make you and your company / product / brand stand out.

If I needed a shortcut model to use, I always used the rule of threes:

One thing they kind of already know to establish credibility and show them you’ve done your homework on their context.

One new thing for discovery or to surprise or challenge them, built off the first thing.

One open-ended thing to give them a chance to respond.

Be ready with tangible examples for them from other customers. Loop back to them what they say to confirm you understand it. Ask lots of questions.

Slack got invited to speak at a design conference in Copenhagen and somehow I ended up going to speak to an audience closer to 600. What did I know about design that I could credibly convey to designers? Near enough to nothing.

But I did know some things about the design process we’d used working on features with customers — the needs gathering and people management and communication work to set the context and then support the design work and launch it to try to make it successful. Let’s call it the work around the design.

So I invited a teammate in our product management team (thank you, Mat Mullen!) to help and we focused on how Slack built, tested, launched and instrumented new features. We showed people an overall generalized process we used at Slack. They we gave them glimpses inside the process for a specific feature to see how everything worked (and didn’t work).

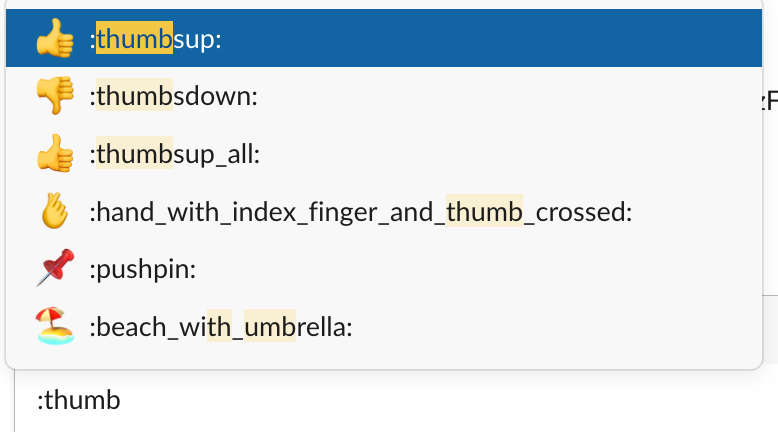

Ever wonder how the emoji reactions feature got conceived, created, tested, recreated, retested and then pushed out into the world? That’s what we covered and it seemed to land well.

Matt played a starring role remotely through short videos and I bridged those videos, setting them up and then joining them together for attendees, then handling any follow up questions. Some questions required me to make a note to get back to folks with a credible answer. Through this tag team with Matt I learned that my new role often was simply to play host and let our talent shine through.

In Madrid we got invited to present at an innovation conference for governments and I partied at the US Consulate. In Paris we got invited as part of LVMH’s Innovation Days to present to their global business teams as part of an internal conference they hosted.

Almost all of these opportunities weren’t direct sales opportunities, but they could lead to direct sales opportunities. They felt like very small scale marketing efforts in closed rooms to mostly exactly the key decision makers we wanted to reach. I just had to be approachable, trustworthy, courteous and curious.

Was it lucky to be seated next to the head of banking innovation at Santander in Madrid? Of course. And then we had a terrific conversation about his home in the Cantabria region, in the town of Santander, where the bank originated, and how hard it was to gather all his family for a week together for Christmas, and how he still loved to cook them all a stew of crawfish, prawns, mussels and clams whenever they showed up.

Learning To Do By Doing

The travel I did and connections I made grew and we started to build a machine to support it. Some combination of the times we lived in and our product momentum and our PR activities and our ability to splash out resources (to answer invitations and coordinate getting there and send someone in person to present) meant we had a chance to have these conversations.

But we had a limited roster of public-speaking representatives. Tier 1 opportunities went to Stewart. No question. He was the star. But Tier 2 and smaller opportunities in Europe, I started to pick up.

It would be too lofty to say that I felt like a missionary ranging out to hostile lands to find new converts. But it also kind of felt like that too, at times. I didn’t face lashing storms or howling wolves or torch-bearing locals. I faced a different slate of engrained beliefs — skepticism, cynicism, conservatism — as well as a general distaste or distrust of US technology.

Yet still, people kept aligning Slack with their innovation initiatives and strategies. People wanted to see new things. People wanted to feel connected to a product like Slack, positioned as the future of work. So, pushing on an open door being easier than one that’s closed, I started framing Slack use as a driver of innovation in two ways that complimented each other. I had stories on how Slack = innovation.

The first way Slack use drove innovation was explicit — through improved work and speed of execution, the classic productivity benefits we could see happening in all our customers. Knowledge work improved with Slack versus email.

The second way Slack use drove innovation was implicit. Slack acted like an internal signal to teams, saying to them that they were expected to work in new ways, open to each other, focused on collaboration, connected to digital tools. Slack showed them they could innovate. Slack had baked-in values that could be smuggled in to organizations to drive change.

And it was convenient for me that both these stories were generally true. Slack did help and Slack did signal. Years earlier we’d seen companies put “…and you’ll work in Slack” as a benefit in job listings. Here were the echoes of that same sentiment.

But here we get to the pickle of setting: most of the work I needed to tackle lived in North America yet I still lived in Dublin and wouldn’t relocate for a few months. So what work could I do to get, as the Irish say, stuck in?

Actually Doing EBCs

Yes, doing the thing. The scary but essential thing I could do from Dublin to get stuck in to the new job was to lead a series of briefings in our London Executive Briefing Centre (EBC).

The full fit out of our London office had been completed and its Radio BBC vibe scaled through the building to our EBC on the mezzanine top (6th floor). With the London sales team we built a briefing series around the Slack Product Security Roadmap — catnip for large enterprises.

We had our Chief Information Security Officer (CISO), Geoff Belknap, visiting the office and took advantage of his geographic availability to queue up briefings with British Petroleum, the British Museum, Sky, the BBC and more prospects and customers who wanted to meet Geoff. Inside each of these organizations we had a foothold of users and room to grow.

Security, whether our customers had flagged it to us or not, always proved to be a sticking point for Slack use and expansion. It made customers feel uneasy. After all, could they really trust this little startup to handle all their internal communication — jokes and ‘where are we going for lunch’ as well as 5-year strategic plans and ‘here’s why we have to fire John.’

We found through the Slack Product Security Roadmap briefing series, and subsequent ones we ran, that when we led our customers to the security conversation we were way more likely to succeed with the security conversation. When a customer felt like they had initiated the security conversation we had much less success.

It reminded me a bit like taking out a new date as a teen. Asking ‘What time should we be home?’ meant the answer was 11 pm. Not asking or ducking the question meant the answer was 10 pm. Asking for boundaries got us more freedom. Not asking and having boundaries imposed on us meant those boundaries were tighter. We would have never learned so early to seek out the security conversation if we hadn’t stumbled onto the success of seeking it out because we had Geoff in town and tried out the briefings.

And that leads me to this. If I’ve ever found an overarching theme to how I like to work, this would exemplify that theme: Learn to do by doing.

I had to do the thing to really learn how to do the thing. So I got started with what I had, in the place I was, before I could get back home. And that’s another story.

Up next: Back in the Slack YVR — Returning to Vancouver. Resetting with Slack YVR. Getting out to SF, NYC and onwards.